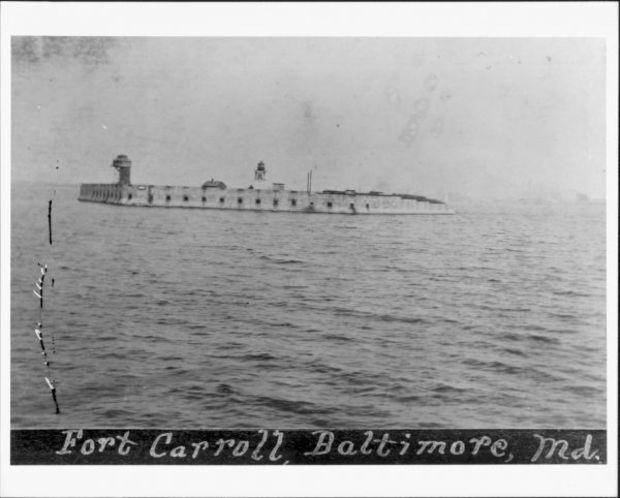

Fort Carroll is an abandoned 19th-century military installation, built on an artificial island, in the Patapsco River. It lies southeast of the Francis Scott Key Memorial Bridge in Baltimore.

During the early 1800s, Baltimoreans called for a new fort to be built to protect Baltimore Harbor (the War of 1812 still fresh in everyone’s mind) that would supplement the protection afforded by Fort McHenry. Construction began in 1848. Initial plans were rather ambitious, calling for a four-story structure of tiered galleries, capable of housing 350 cannons. The project supervisor was brevet-colonel Robert E. Lee of the Army Corps of Engineers, and future commander of the Confederate Army.

Fort Carroll was Lee’s first command. For three years, he supervised the fort’s construction, and in 1850, it was named in honor of Charles Carroll, a highly influential Maryland politician and the last living signer of the Declaration of Independence.

By 1851, after spending $1 million, construction was far behind schedule. Only the structure’s foundation and first level had been completed. While Congress debated future construction, Lee grew impatient and accepted a new position as the head of the West Point Military Academy.

Progress continued to move slowly, but a year later Congress provided $1500 for a beacon light to be built at the site. In 1854, a small keeper’s dwelling with a light atop its roof was erected to warn ships of the large construction site and to indicate the path from Brewerton Channel to Fort McHenry Channel. By the time of the Civil War (1861-1865), the fort’s walls were less than half of their originally designed height. Regardless, 30 guns were placed inside the structure to protect Baltimore Harbor from Confederate incursions. And while no hostile shots were actually fired during this time, the guns remained trained on Southern forces that Lee now commanded.

In 1864, heavy rains flooded the island, creating unsuitable conditions for the stored weaponry. All of the ammunition and gunpowder was moved to nearby Fort McHenry. As the years passed, the look and purpose of the fort continued to change. In 1875, the light and bell from the roof of the keeper’s dwelling were removed and transferred to a new wooden tower built on the southwest wall. In 1888, a new keeper’s dwelling was constructed. A year later a new lighthouse was built, the one still seen today.

During the Spanish American War (April 1898-August 1898), the recently built light and fog bell tower were demolished to make way for more concrete gun batteries. But as with much of the fort’s construction, progress was slow, and by the time the guns were in place in 1900, hostilities with Spain had ceased.

Later during the two World Wars, Fort Carroll served varying purposes, such as a practice firing range or barracks for foreign sailors, but never saw true combat. By the early 1920s all guns were removed, the lighthouse was automated, and the fort itself became virtually obsolete. The army sold the property in 1958 to Baltimore lawyer Benjamin Eisenberg who hoped to one day turn the island into a casino. These plans were never brought to fruition, and after other business ventures failed over the years, the fort continued to sink into disrepair.

The Fort Carroll Lighthouse remained active until 1964 when it was put out of commission by vandals and subsequently never repaired. Today, the only residents of Fort Carroll are a large colony of birds that nest in the abandoned peach trees (another failed venture) inside the island’s walls. Politicians, environmentalists, and local interests continue to debate the future of the island but any decision has yet to be made. In 2015, Fort Carroll was listed on the National Register of Historic Places.