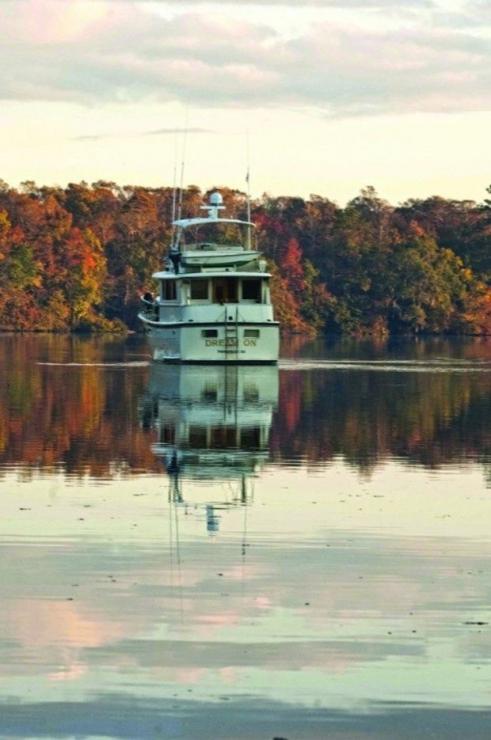

Just getting there is more than half the fun, when you’re cruising south on the Intracoastal Waterway (ICW), a 1243-mile waterway that connects rivers, canals, sounds and land cuts on the Atlantic coast.

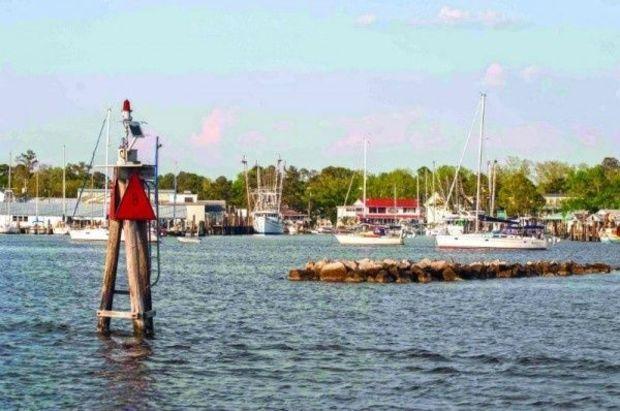

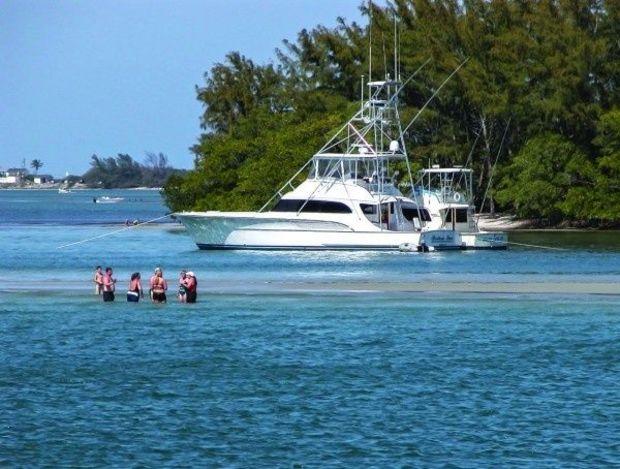

The ICW is a continuous navigable waterway from Norfolk to Key West strung along the eastern seaboard—passing through, Virginia, North Carolina, South Carolina, Georgia and Florida—is one of our favorite cruising grounds. In the fall of any given year you’ll find the perennial snowbirds using the Waterway to head south with Midwest and Canadian hailing ports. Along the way they meet cruisers from the East Coast and delivery crew on mega yachts following the sun, many bound for the Bahamas and Florida ports of call. We’ve made the passage 13 times beginning in 1975 from Chicago and most recently in October, 2012, from our home waters at the Miles River YC in St. Michaels. While we’ve seen many changes in the spread and growth of the maritime harbor towns, the beauty of natural wildlife areas and lush landscape remains the same. The shoreline includes a wide range of marina facilities and protective anchorages for any size power boat. And you won’t be alone given that the AICWA, the Atlantic Intracoastal Waterway Association, estimates 12,000 recreational boaters, transient and local, will be using the Waterway in the coming year.

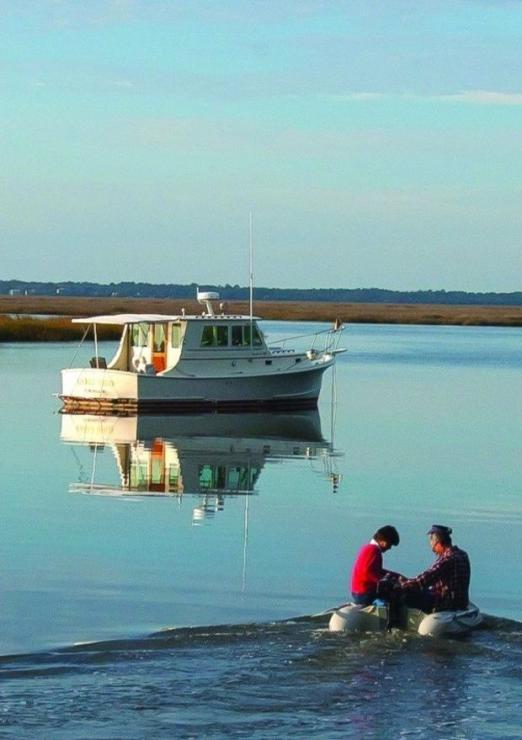

Cruising the ICW can be a very social affair because you soon find you’re seeing the same boats at the end of the day. Whether you’re holed up in a snug anchorage or tied in a marina you’ll find other boaters who travel the same distance y ou do, and you’ll probably share a “docktails” together and discuss the day’s run and what to expect the next. The charming harbor towns and picturesque anchorages make it easy to spend days in one place. And times goes by easily while underway as you pass by a variety of terrain and shoreline. The dark tannin waters and miles of secluded tree-lined riverbanks give way to turquoise ocean water and white sandy dunes at sounds and inlets. Populated areas are a virtual house walk of elegant mega homes, many with elaborate boat houses and boats while small cottages dot the shoreline in more remote areas. If you’re considering doing the “Ditch” (as the waterway is sometimes called), here’s our best advice on planning, scheduling, boat handling, and budgeting, for an ICW adventure.

A Time Frame for Intracoastal Waterway Travel

Most cruisers leave the Chesapeake Bay in mid-October, after a stop at the Annapolis Power Boat Show or Trawler Fest in Baltimore. Depending on your boat insurance your coverage may be limiting because many companies stipulate being north of Cape Hatteras until November 1, when the threat of hurricanes decreases. If you plan an earlier departure you can buy a rider that extends the coverage.

Your Daily Run

The length of time it takes to cruise the ICW depends on your destination, the speed of your boat, bridge openings, and your cruising style. If you’re going to Marathon, FL, at mile 1193 in the Keys you have 1193 miles to go from Norfolk at Mile 0. Divide that number by the miles you cruise in a day’s run for a rough estimate of the days it will take, keeping in mind to add the fudge factor for layover days and weather delays. If you’re in a hurry, your cruising style will be more like a delivery crew; if not, you can take time to visit an area and friends along the way. If you have a change of crew or plan to leave the boat half way, consider harbor town with an airport nearby. Bridge openings are another consideration but when you know your speed you can factor in the openings.

Use a cruising guide such as Waterway Guide’s Atlantic Intracoastal Waterway edition for a listing of bridge locations (statue mile on ICW) with time openings and restrictions and clearance of bridge when closed. Know your boat’s air draft—the distance from the surface of the water to the highest point on a boat—to see if you require an opening. The tide boards at the bridge shows the clearance depending on the state of the tide. As you go from state to state you’ll switch from VHF channels to talk to bridge operators. Channel 13 is used by bridge operators in Virginia, North Carolina and Georgia, while South Carolina and Florida use Channel 9. A cell phone operates in most stretches of the waterway except in some remote areas where service can drop. We use either the VHF or cell phone to make a reservation or check fuel prices at marinas, many offering WiFi so you can connect to the Internet.

Staying in the Channel

Charts of the ICW show a magenta line to use as a guideline between the red and green markers of the Waterway. It’s a helpful aid especially to look ahead on a long stretch or where two bodies of water connect, like the intersection of the ICW with St. Lucie Inlet or crossing the Savannah River. But we consider the line an aide (not gospel) and take temporary buoys more seriously, having seen boats hard aground where the magenta line is indicated on the chart. The numbered red and green marks line the shoreline of the Waterway. When going south, “red, right, returning” is not always the rule to follow. The exceptions are when the Waterway crosses an inlet or enters a river system, so there can be confusion. For example, in North Carolina going south the ICW channel enters the Cape Fear River. The red ICW markers move to the left side of the river channel because you’re traveling toward the ocean; later you re-enter the waterway and the reds are back on the right.

Using Radar

Set the unit to “Heads Up” mode so the screen reads zero at the top and 180 degrees at the botton. Set an electronic bearing line (EBL) to point toward the bottom of the screen or to 180 degrees relative. The heading marker will run from the center to the top of the screen, while the EBL runs from the center to the bottom. You stay in the channel by steering the boat so the heading marker is aligned with the marker off the bow, and the EBL is aligned with the marker you just passed. If the boat begins to drift out of the channel, you’ll notice as the lines on the screen move away from the marks.

Running Ranges

A range is a navigation aid designed to help commercial vessels stay in the channel at long stretches of a river and at bends and curves in the Waterway. While some have been damaged, those that remain help cruisers, too. On paper charts they’re clear boxes, and on electronic charts are red and white horizontal bars. The structures on the shore or in the water are large markers usually painted in red and white vertical strips that form a pair of front and rear markers. By aligning the stripes, you know if your boat is in the channel or not. If the front-range marker begins to appear to move to the right the boat is drifting toward the left side of the channel. To get back into the center of the channel, steer to the right until the marks are again aligned. Remember: steer toward the front marker of the range to return to the center of the channel.

Passing & Being Passed

Communicate with a boat you want to overtake on the VHF or a horn toot (one for a starboard pass, two for a port pass). Don’t slow down until your boat is near, then go as slowly as the other boat allows. When it’s safe to move your boat in front of the boat passed, accelerate to your cruising speed. If you’re passing a tug or commercial vessel, call and ask if the skipper prefers that you pass on one side or the other, because he’s less maneuverable and has a deeper draft. When you have to pass by a working a dredge, confirm which side the dredge operator wants you to pass. If there’s no reply to your call pass on the side of the dredge displaying the two vertical diamond shapes that signal ‘safe passage.’ When you’re the boat being passed, slow down as the overtaking boat closes in on your stern and cut the throttle to idle speed. When the boat safely passes, move in behind it before it accelerates to avoid a large wake you’ll have to negotiate.

Anchoring Out

There are countless safe anchorages along the ICW, in the wide open rivers and creeks where one anchor with chain is enough to handle the tidal range. In rivers, where your anchor may be fouled by an old tree stump, we use a trip line float on the anchor line to protect the line. In southern low country, strong tidal currents sometimes require using two anchors set in a Bahamian mooring system to reduce the swing of the boat while allowing it to move 180 degrees and face the changing current. We use an anchor sentinel with a light drop weight to prevent the anchor line from getting tangled on the prop or rudder when the boat swings.

Docking & Locking Through

We have great respect for the current when docking especially in the Carolinas and Georgia. The current always wins against the wind, so we’re not bashful about calling a marina and asking for the best approach to the dock. You can use the current to your advantage by bowing into it and having fenders tied vertically so they’re about eight to ten inches above the water. We use a spring line secured to a cleat amidship and hand it to a dockhand to secure. Then the helmsman turns hard over away from the dock and boat moves against it with time to secure a bow and stern line.

Going Through a Lock

Just south of Norfolk, you choose between two routes: both lead to Albemarle Sound and the Alligator River. The Virginia Cut has one lock at Great Bridge and is slightly shorter; the more scenic Dismal Swamp with two locks is a step back in time but can be prone to shallow water, depending on rainfall. When you approach a lock, you’ll see an arrival point with instructions to wait for a green light to enter the lock. Call the lockmaster on Channel 13 and request to lock through. Ask if there are lines in the lock or if you use your own, and which side of the lock to tie to so you know where to hang fenders. When the lock opens, have crew on the bow and stern to pick up a line on the lock wall or secure one from the boat around a bollard. With our boat’s crew of two, as we approach we decide which line to grab or bollard to use and Katie goes to the bow with a boat hook and picks up a line (or secures one), while Gene stops the boat and moves to the stern to pick up a stern line (or secure one). We fend off the boat with boat hooks until the lock has completed its cycle and we can cast off and get underway.

About the Authors Katie and Gene Hamilton are authors of Cruising the Intracoastal Waterway and Lessons Learned Cruising the Intracoastal Waterway

For more information on cruising the ICW, check out our other great articles!