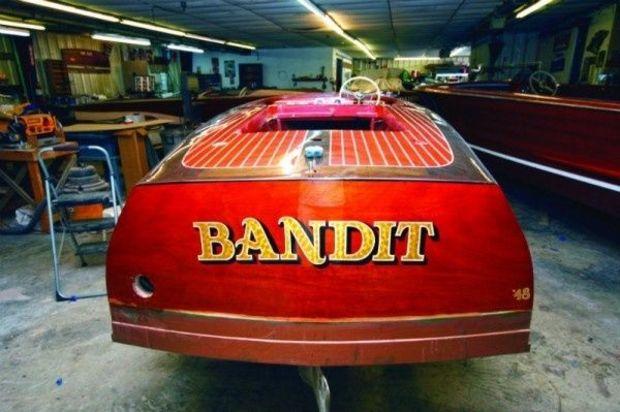

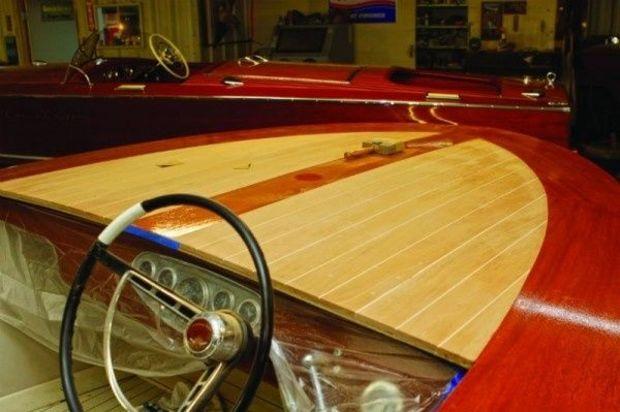

Wooden boat owners: people often use words like “crazy,” “insane,” “eccentric,” or even go so far as to pull out the “stupid” card to describe them. But let’s remember that fiberglass boats aren’t without their problems: blisters, delaminating hulls, water-soaked cored decks, and rudders included. We might poke fun at the wooden boat crowd, but few of us are immune to the beauty of a restored classic. Upon the mere sight of the varnished glossiness of one, most boat-minded folks enter a trance-like state where they pore over every detail of the subject boat and use adjectives like “beautiful,” “gorgeous,” and “unbelievable.”

But let’s say (for the sake of conversation) you are actually considering buying and restoring a wooden classic boat. Or maybe you already own one that is in need of repair. Unless you are versed in what to look for, you can get yourself into deep trouble fairly quickly. So PropTalk decided to hunt down an expert and find out the potential pitfalls and possible pleasures of purchasing and restoring a wooden classic. That search led us to George Hazzard of Wooden Boat Restoration in Millington, MD.

Never Let Your Emotions Override Common Sense

I met Hazzard in the back of his shop, and he immediately started out by telling me a story about one client who was looking to buy a wooden classic and said he already had his eye on one. “This guy had a boat he wanted to buy and asked me if he should buy it or not. I told him that I’d be happy to look at it with him, but by the time I talked to him next, he’d already bought the boat. The next week I went down to launch it with him and as we rolled the boat back into the creek, water started seeping in from the transom. Then we tried to start the engine and it wouldn’t.” The buyer’s impulse purchase ended up costing him about $20,000 by the time the boat was made right again.

Unless you’re willing to invest a lot of money, it’s never a good idea to let the apparent beauty (or your potential vision of what the boat will become) cloud your vision. If you do find a boat you are interested in, it’s time to do some Sherlock Holmes-style digging.

Poke Around, Then Poke Around Some More

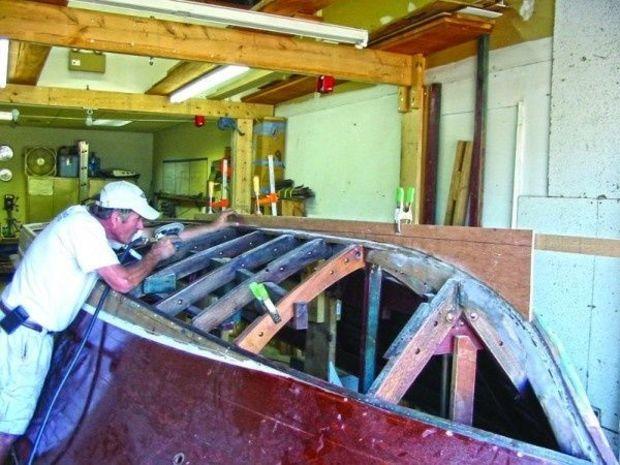

Wooden boat buyers often fail to know where to look for telltale signs of damage, but with a little poking around, one can stave off potential heartache. “If the seller won’t let you lift up the floorboards and have a look around, walk away,” Hazzard says. He then led me over to an old 30-foot Chris-Craft Constellation that was upside-down in his shop without any bottom planking. Hazzard then reached his hand through the boat’s exposed frames and pointed at the engine stringers, which looked fine to me. “See those?” Hazzard then proceeded to push his finger almost straight through a section of one of the engine stringers and pulled out a small handful of material that resembled garden mulch. “You really have to look around and try to find rot; it doesn’t just pop out at you.”

For another example, Hazzard walked me outside to a beautiful skiff that was sitting on a trailer. Hazzard started pointing around and showing me the bad news. The stem was mush, there was rot all around the rubrail into the plywood topsides, pieces of end-grain mahogany had been patched into the corners, and a brace job on the transom didn’t even physically connect with it.

Hazzard offered me a long list of suggestions: “If the boat has been on a trailer for a long time, look for damage caused by the trailer’s rollers, as the weight of the boat often causes the rollers to leave dents or damage to the hull and frames. Pull up all the floorboards and have a look around the stringers, frames, planking, and transom. Push your finger into the stringers, frames, stems, and support pieces to check for rot. Look for bubbled up paint or varnish; this usually means there is water damage or rot underneath. And if you can, get an expert involved.”

Be Realistic About the Costs

A big mistake that people sometimes make when getting involved in a wooden boat project is underestimating the costs. It can easily cost a couple thousand dollars a week in labor, material, and storage costs to carry out a full-on restoration. The lingo in the boat business is: “make an estimate and multiply times two.”

Unless you’re willing to invest a lot of money, it’s never a good idea to let the apparent beauty (or your potential vision of what the boat will become) cloud your vision. If you do find a boat you are interested in, it’s time to do some Sherlock Holmes-style digging.

Poke Around, Then Poke Around Some More

Wooden boat buyers often fail to know where to look for telltale signs of damage, but with a little poking around, one can stave off potential heartache. “If the seller won’t let you lift up the floorboards and have a look around, walk away,” Hazzard says. He then led me over to an old 30-foot Chris-Craft Constellation that was upside-down in his shop without any bottom planking. Hazzard then reached his hand through the boat’s exposed frames and pointed at the engine stringers, which looked fine to me. “See those?” Hazzard then proceeded to push his finger almost straight through a section of one of the engine stringers and pulled out a small handful of material that resembled garden mulch. “You really have to look around and try to find rot; it doesn’t just pop out at you.”

For another example, Hazzard walked me outside to a beautiful skiff that was sitting on a trailer. Hazzard started pointing around and showing me the bad news. The stem was mush, there was rot all around the rubrail into the plywood topsides, pieces of end-grain mahogany had been patched into the corners, and a brace job on the transom didn’t even physically connect with it.

Hazzard offered me a long list of suggestions: “If the boat has been on a trailer for a long time, look for damage caused by the trailer’s rollers, as the weight of the boat often causes the rollers to leave dents or damage to the hull and frames. Pull up all the floorboards and have a look around the stringers, frames, planking, and transom. Push your finger into the stringers, frames, stems, and support pieces to check for rot. Look for bubbled up paint or varnish; this usually means there is water damage or rot underneath. And if you can, get an expert involved.”

Be Realistic About the Costs

A big mistake that people sometimes make when getting involved in a wooden boat project is underestimating the costs. It can easily cost a couple thousand dollars a week in labor, material, and storage costs to carry out a full-on restoration. The lingo in the boat business is: “make an estimate and multiply times two.”

Some shops will allow you to work with a monthly budget, where you can specify the dollar amount of work you want to occur each month, but don’t expect this as the norm; some won’t even pull your project into the shop without a full-on monetary commitment from the start.

Lastly, sometimes it makes more monetary sense to buy a boat that is already restored, if you’re not interested in the restoration process itself. “You really have to be into the process and love the boat to commit to one of these projects. Sometimes it’s better to just buy one that’s already been restored; just make sure that’s what she really is, though,” Hazzard says. (See the aforementioned “poking around” section.)

An Expense, Not an Investment

Hazzard tells me that some clients expect to make money on a restoration, but explains that this almost never happens. “Lots of people buy a classic wood boat at a super deal and then expect to have a real beauty that they can sell at a profit,” Hazzard says. “It just doesn’t work that way, no matter how good a deal the buyer gets.”

“There’s a reason they’re called pleasure craft. And remember that boat is a four-letter word,” Hazzard explains with a grin. “You have to do it because you love the boat and the process. Look at this one (he points to an old powerboat)—it’s a family heirloom, so they’re restoring it to save a piece of their family history. These folks over here have had this boat since it was new, so they love it. That’s the right approach,” says Hazzard. Hazzard’s last piece of advice: “Don’t expect to get rich buying and selling classic boats.”

Get an Expert Involved

Some shops will allow you to work with a monthly budget, where you can specify the dollar amount of work you want to occur each month, but don’t expect this as the norm; some won’t even pull your project into the shop without a full-on monetary commitment from the start.

Lastly, sometimes it makes more monetary sense to buy a boat that is already restored, if you’re not interested in the restoration process itself. “You really have to be into the process and love the boat to commit to one of these projects. Sometimes it’s better to just buy one that’s already been restored; just make sure that’s what she really is, though,” Hazzard says. (See the aforementioned “poking around” section.)

An Expense, Not an Investment

Hazzard tells me that some clients expect to make money on a restoration, but explains that this almost never happens. “Lots of people buy a classic wood boat at a super deal and then expect to have a real beauty that they can sell at a profit,” Hazzard says. “It just doesn’t work that way, no matter how good a deal the buyer gets.”

“There’s a reason they’re called pleasure craft. And remember that boat is a four-letter word,” Hazzard explains with a grin. “You have to do it because you love the boat and the process. Look at this one (he points to an old powerboat)—it’s a family heirloom, so they’re restoring it to save a piece of their family history. These folks over here have had this boat since it was new, so they love it. That’s the right approach,” says Hazzard. Hazzard’s last piece of advice: “Don’t expect to get rich buying and selling classic boats.”

Get an Expert Involved

Does all of this sound confusing and scary? The best thing you can do is to get an expert involved in the purchase process. Have a look at PropTalk’s Boatshop Reports section each month, and you’ll find several Bay-area shops and builders who specialize in wooden boat restoration. “I’m always happy to help prospective buyers by looking at the boats they are thinking about getting involved with,” says Hazzard. “It’s an excellent way to remove some of the anxiety of trying to spot everything yourself.”

So why would anyone ever be crazy enough to get mixed up in something like this? There are usually lots of reasons, some sane and some of them off-the-wall, but it’s usually for the love it, of course. There’s really no other reason to get involved in a wood classic project unless the entire process appeals to you—from acquisition, to restoration, and on to launch where you’ll parade proudly down the creek to the envy of standers by.

Don’t say we didn’t call you crazy and brilliant for doing it.

Does all of this sound confusing and scary? The best thing you can do is to get an expert involved in the purchase process. Have a look at PropTalk’s Boatshop Reports section each month, and you’ll find several Bay-area shops and builders who specialize in wooden boat restoration. “I’m always happy to help prospective buyers by looking at the boats they are thinking about getting involved with,” says Hazzard. “It’s an excellent way to remove some of the anxiety of trying to spot everything yourself.”

So why would anyone ever be crazy enough to get mixed up in something like this? There are usually lots of reasons, some sane and some of them off-the-wall, but it’s usually for the love it, of course. There’s really no other reason to get involved in a wood classic project unless the entire process appeals to you—from acquisition, to restoration, and on to launch where you’ll parade proudly down the creek to the envy of standers by.

Don’t say we didn’t call you crazy and brilliant for doing it.