When Tom Mrazik stepped up to board the Coast Guard response boat from what remained of the submerged stern on his now very much wrecked vessel—he was pretty sure his bourgeoning nautical career was completely over.

Charlotte, Tom’s wife of 30 years and eager first mate, was already aboard the Coast Guard response boat with the authorities and soaking wet in her lifejacket. She had drifted nearly half a mile in the current and waves before the response boat met her, because when she disembarked her sinking vessel, she did so on the windward side accidentally.

Safely reunited aboard the response boat and en route to the Coast Guard station, after what had felt like living the dream turned suddenly into every boater’s worst nightmare, Charlotte and Tom had little more than the shirts on their backs.

“We’re going to get another boat, right?” she said, much to her other half’s relief.

The couple had just traded in their golf clubs, golf cart, and the keys to their 2500-square-foot home on a golf course in Texas for full-time life aboard on a 45-foot, twin diesel Carver 455 they named Outlander. They were several months and well over 1000 nautical miles into their maiden cruise complete with precise navigation of extensive shipping lanes and successful offshore overnight jaunts. They cruised from Texas’s Gulf Coast to the Mississippi River Locks, locking through with commercial sized barges, to the Okeechobee Waterway in Florida, and up along the Atlantic Intracoastal Waterway.

“We left with minimal sea time, but I didn’t consider myself too naive,” Tom said.

“Before we left, I replaced all the through hull fittings with real Grocko marine seacocks and new raw water hoses; all high-quality marine gear. I thought it was the right thing to do to keep it afloat.”

Rough Seas on the Pamlico Sound

The trip was cut short on the infamous Pamlico Sound in North Carolina, just shy of their intended destination on the tidewaters of the Chesapeake Bay, where their grown daughter, son-in-law, and new grandbabies awaited them.

Notorious for steep, short waves with an incredibly shallow bottom and rich history of pirate shipwrecks, the 80-mile-long Pamlico Sound’s southern exodus intersects the ICW. Suffice it to say that northerly winds can kick up quite a chop before the waterway turns west into the protected Bay River and Bay River Canal.

It had been a peaceful night tied up in Oriental Harbor, a popular cruising stopover. There was a steady breeze as they got underway that Tom estimated at 20 knots on the nose, which wasn’t ideal but certainly doable. However, the winds intensified as the fetch of waterway opened up.

“Should we turn back?” Charlotte said.

“That night in Oriental was our last night on the boat,” Tom said. “We just didn’t know it. We were only going to Bellhaven and didn’t think much of it.”

This wasn’t Tom and Charlotte’s first rodeo. (No pun intended, but the pair did own a ranch at one point so their daughter could train for exactly that.) Later they would learn the wind gusts peaked at 38 knots out of the northwest that day, but without any wind instruments they pressed on. Plus, the waves had built to what Tom described as six to eight feet. He felt more comfortable taking the waves on the bow than risking turning around.

Now on the Pamlico River, a 12-foot shoal needed to be cleared to port. To starboard was the 20-foot-deep channel being pummeled by winds and waves funneling down the Sound. Tom and Charlotte’s eyes were glued to the depth finder and holding on. Suddenly, the oil pressure alarm went off and one engine shut down. Tom couldn’t leave the helm to investigate but was formulating a plan to limp into the protected river after clearing the shoal on the remaining engine… when it went out as well.

Dead in the water, Charlotte took the helm and Tom went to alert the Coast Guard on the VHF that they were a disabled vessel and to check on the engine room. When he lifted the stairs to the engine room, he saw water already up to the hatch and ran back to the VHF to declare a real emergency, as they initially put out a Pan-Pan.

Literally like the scene in Titanic where a bewildered Rose scours the belly of the sinking ship for her lover Jack, Tom was chest-deep in water in the engine room closing seacocks. But that didn’t stop the water from coming in and the Pan-Pan quickly turned into a Mayday.

Still taking on water, now up to the salon, Outlander’s crew was in luck. They had drifted up and wrecked on the shoal they were trying to clear, instead of in deeper water that would have swallowed them whole. Plus, the Coast Guard’s Hobucken Station was a mere few nautical miles away and its squadron jumped enthusiastically into the mission. It was the last day of their rotation, and first ever Mayday.

The rescue mission wasn’t so straight forward. The response boat bumped the shoal. Charlotte jumped overboard and drifted away. One coastie was puking. Another was nearly decapitated by a tow line. And yet everyone remained calm the entire time. The AGM batteries and VHF miraculously never shorted out and a few hours later the Mraziks were shoeless on land, wrapped in flannel blankets, sitting in plastic garden chairs while they waited for their family to come pick them up.

“We were never really worried thanks to them,” Tom said in regard to the seamanship exemplified by the Hobucken Coast Guard Station. “It’s just a boat. We knew we would be okay.”

On May 30, 2020, at approximately 10:30 a.m. the M/V Outlander was on the bottom. And by 9 p.m. the next day she was salvaged, raised, pumped out, and declared a total loss. There was nothing left.

Tom and Charlotte wasted no time looking for their next boat and by the Fourth of July they were happily moved aboard a Carver 504, the exact same boat but with a cockpit, a few more feet, three years newer, and cheaper than the last!

“It doesn’t always pay to sink your boat,” Charlotte joked.

Redemption

Aptly named Redemption, Tom has become obsessed with making this boat more seaworthy than the last while honing his seamanship skills. To this day they still aren’t sure exactly what happened—if they hit bottom because of the size of the waves, or unknowingly had hit the shoal earlier, or if it was the force of the waves alone that damaged the hull. All they know is that what ultimately sank her was the caving in of the engine room vents as the hull flexed and the vents were pounded.

Straight out of the factory, the vents on the Carver were just screwed directly into the hull. Onboard Redemption, Tom removed the grates, reinforced the hull with epoxy and fiberglass, then tapped, threaded, and through-bolted the aluminum frames back on. And he hasn’t stopped there.

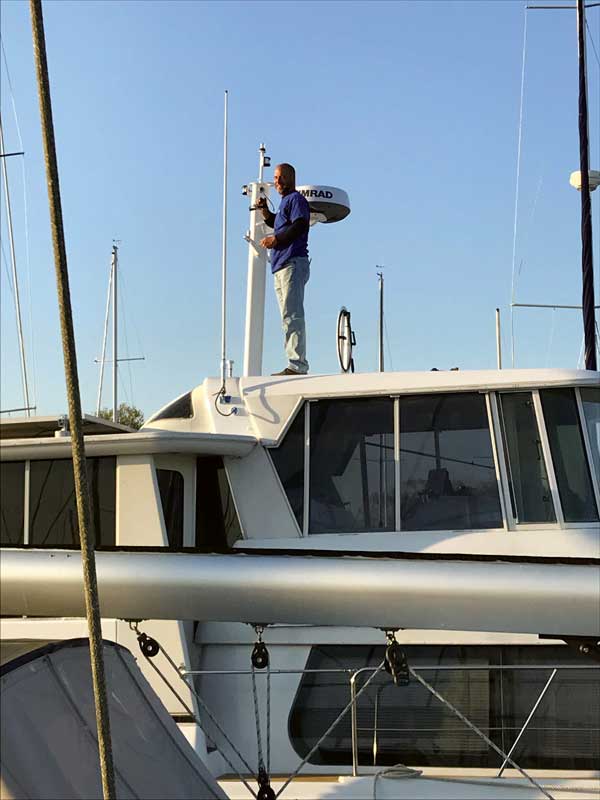

Remote control Simrad autopilot, Vesper AIS, a new Simrad Halo24 Radar with a custom-built mount that looks like a mast for a stabilizing sail, 3200 watts of solar and lithium batteries, new bomber hatches… the list goes on.

“We are trying to take the lessons learned from sinking and make sure that when we do take off cruising again—to the Bahamas, the Great Loop… that we have done all the proper preparations,” Tom said.

What haunted him the most about the incident was that when they had done their first offshore passage a season earlier from Carabel to Tarpon Springs, a 140 nautical mile overnight run in the Gulf, the conditions were similar to what they were that day on the Pamlico Sound. It was a rough passage; Tom gripped the helm the entire night and Charlotte held on as the boat rocked heavily. They had waited for good enough weather, they’d thought. They’d filed a float plan. But they never expected heavy weather.

“The moral of the story is it could have happened there. We had no electronics that worked that far offshore,” he said.

Docked safely now in Herring Bay, Tom is enjoying working as a marine electrical tech after a long career in Texas oil, and Charlotte is managing a doctor’s office which she did for 24 years in Texas—before they got the itch to cut the dock lines.

“I don’t do my job for the money anymore. I do it because I love it,” Tom said before Charlotte chimed in.

“Well, you do it because we need to eat,” she said.

Their daughter, son-in-law, and grandbabies are a convenient 45 minutes away. Life is good and Redemption is safe in the harbor as they refill the cruising kitty, but Tom and Charlotte both know ships are not meant for the harbor.

“You spend all your adult life finding and buying and building and selling houses, having jobs, cars…” Charlotte said. “Build a house, get property, get the country club membership. All that stuff. Our goal in life is to simplify. Get rid of all that.”

“I’d rather eat burgers than ribeye,” Tom said stretching out his arms and pointing out at the Cliffs of Herring Bay.

“Look at my backyard. I’m happier now.”

By Emily Greenberg