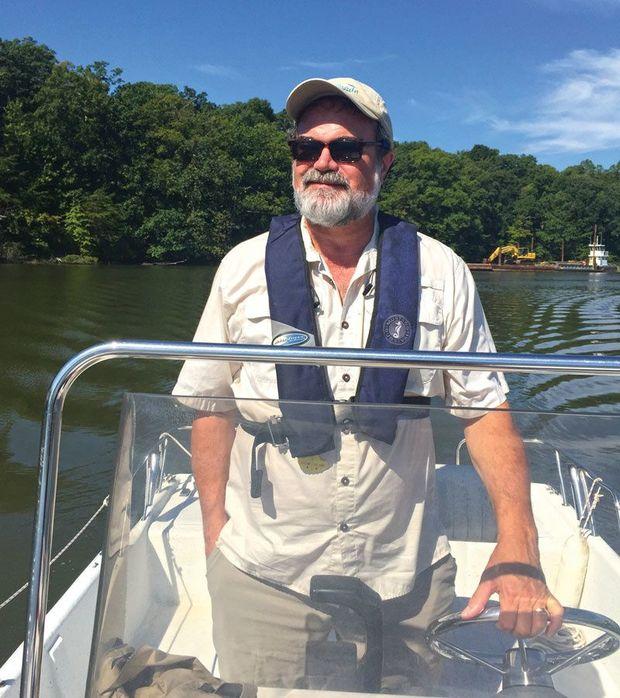

Raising awareness about the importance of the Chesapeake Bay, its ecology, and history have been in large measure the focus of Jeff Holland’s professional career. Though Holland was raised in the Pittsburgh area, he began coming to this part of the country with his father in the early 1980s to charter sailboats in the summer. One year, partway through a grand boating adventure from the Great Lakes to Florida, the father and son duo stopped in Annapolis. They found the historic sailing town so appealing that they saw no need to continue their journey. More than three decades later, Holland is still in Annapolis. His hair and full beard, once dark brown, are now mostly silver, and with his cap and sunglasses, he looks every bit the part of a Bay-loving outdoorsman.

All roads lead to the West and Rhode Rivers

“This position connects all I’ve done over my career,” says Holland. “I like to create projects to educate people about why we need to protect the water. For four centuries the water has impacted the lives of people in this area, and for four centuries people have impacted the water. Riverkeepers depend on the people who boat and live here to be our eyes and ears, so we can be the voice of the rivers. It took a million thoughtless acts to get us where we are today, and it’s going to take a billion thoughtful acts to restore the Bay. It’s what I’ve been working on for 30 years.”

Though his jobs have been varied, their common thread has been the water, starting with his own public relations firm, which led to a spot at the Annapolis Boat Shows as director of public relations and a stint with the Annapolis Sailing School. A volunteer at the Annapolis Maritime Museum (AMM) since 1996, Holland became the museum’s executive director in 2001. Under his leadership the museum’s programs and exhibits greatly expanded, including Holland’s signature MUDDY FEET program, which gives students multiple Chesapeake Bay watershed experiences. In 2003, after Hurricane Isabel struck a devastating blow to the building that housed the museum, Holland oversaw the structure’s recovery and renovation. In 2012 Holland left AMM to relaunch his public relations firm. Shortly thereafter he was named executive director of the Captain Avery Museum in Shady Side, MD.

When he learned by chance that the West and Rhode Riverkeeper’s board of directors was looking for a new executive director, Holland immediately inquired and was offered the job in late 2013. About that same time he became a member of the board of directors for the Great Chesapeake Bay Schooner Race, an annual event in which he’s participated about a dozen times.

Of home and relaxation

Holland lives in Annapolis with his wife of 34 years, and their Irish setter and fat cat. The couple are proud parents of one adult daughter. Holland owns a “large fleet of small boats,” including a 17-foot aluminum canoe his father purchased when he was a young boy.

“My idea of heaven is a little boat, a little creek, and a fishing pole,” he says. “I’ve found a few nice places around the Chesapeake Bay Watershed, such as the Monocacy River, where I go to relax. I drive up with my bike and small boat, drop off the boat, drive downstream and park the car, ride my bike back to the boat, and shove off. I cast a line and do some fishing while I float downstream to the car. Then I put the boat back on the car and drive up to get my bike.”

Author and musician

Holland, who earned a B.A. in journalism from Penn State University, has written two children’s books. In 1990 he penned “Chessie, the Sea Monster that Ate Annapolis,” a story about a 42-ton Chesapeake Bay Retriever. And coming out in December will be his latest work, “Charles Carroll’s Cats,” a novella about two Annapolis boys whose cat is catnapped to the Great Poplar Island Cat Farm in 1847.

An avid musician, Holland is a singer-songwriter and was a founding member of Them Eastport Oyster Bays (EOB). “Writing original music inspired by the water, crabs, and old boats is a fun way to get people to start thinking and maybe understand what an incredible treasure we have in our own backyard,” he says. “In high school and college I sang in school and church choirs and acted in musical theater productions. I picked up the ukulele because it was the simplest instrument I could find that I could plunk on and accompany myself on my own songs.”

“Jeff is an accomplished baritone ukulele player, but he excels at the Estonian jaw harp, a mouth instrument that he picked up in Estonia on a goodwill tour about 10 years ago,” says EOB co-founder Kevin Brooks, who met Holland in the late 1980s. For a time they both played in the musical group Crab Alley, and in the early 1990s the two started EOB. Together they wrote about 90 percent of the group’s music. Holland retired from the band about five years ago.

Brooks likes to say, “We tell Jeff that whenever he’d like to carry on the legend with us, there will be a cold mic and warm beer waiting when he shows up.” What kind of music does a Bay-loving songwriter listen to? Holland says, “My music file is an odd array of songs that I listen to regularly and repeatedly, ranging from Benny Goodman’s ‘One O’Clock Jump,’ to Tom Lehrer’s ‘Vatican Rag,’ to the sextet from Donizetti’s ‘Lucia di Lammermoor.’ Just now I’m hooked with ‘Old Man River,’ and listen to renditions by Paul Robeson, Al Jolson, and Frank Sinatra. Other names on my list include my heroes Pete Seeger and Tom Wisner, both of whom I want to be when I grow up.”

Brooks concludes, “Jeff is a funny, sometimes shy, sometimes boisterous, creative, family man who embodies the spirit of the Chesapeake. His legacy will be what he’s written. He’s an excellent writer of prose, lyrics, history, or satire. Jeff’s writing, whether it’s children’s books or the songs we co-wrote for the EOB, reflects his dedication to the Bay.”

by Beth Crabtree