While many Chesapeake boaters may not keep their boats at a dock in their back yard, I would imagine that many have a yard, or piece of property, in the Chesapeake watershed that is impacted by invasive non-native plant species. Many of these species arrived either intentionally, or unwittingly, when the first colonists arrived on the Chesapeake’s shores which might lead some to believe they have always been present in their local ecosystem.

Phragmites (Phragmites australis), also known as common reed, is a perennial aggressive wetland grass that spreads through rhizomes (roots). It is a plant of Eurasian origin thought to have arrived in the early 1800s through ballast water (a common transport method for invasive plant and animal species). Purple Loosestrife (Lythrum salicaria), an herbaceous perennial that overtakes native wetlands, arrived at a similar time period and arrived via ballast, caught up in the wool of sheep, or was brought over as a healing plant. Purple Loosestrife can affect water chemistry in marshes as well as alter the species composition.

Wildlife that depends on native plants for food or nesting is displaced. More recent invasive arrivals have been both intentional (ornamental garden plants) and accidental. Originally thought to be beneficial, invasive plant species are now out-competing native plant species in a variety of ways. They can block sunlight, take up water or nutrients needed by native species, alter soil composition, and strangle native species, particularly mature trees. Mature trees make up healthy, intact forests and are part of riparian buffers that positively impact water quality in the Chesapeake watershed. Nothing can replicate the work that healthy forests do for water quality by controlling erosion and filtering excess nutrients. When invasive vines (such as Kudzu, Wisteria, Oriental Bittersweet, and Porcelain Berry) choke and bring down mature trees, it allows sunlight through to the forest floor and alters the forest ecology and associated wildlife, as well as allowing more invasives to spread.

What defines an invasive plant species? Invasive plant species are recognized by biologists and natural resource managers because they degrade natural ecosystems and negatively affect native species. They lack the disease and predators that they contend with in their native lands so they can proliferate by maturing early and growing rapidly. Even if a native species utilizes an invasive as a source of food, it is not nutritionally equivalent, and migratory bird species end up flying on an empty tank. Forty-five percent of the species listed as Federally Endangered are negatively impacted by introduced species.

Invasive plant species can alter complex trophic associations that have taken years to develop. If an insect depends on a certain plant for survival (think monarch butterflies and milkweed), they are considered a food “specialist.” The removal of that plant from the ecosystem impacts not only the plant but the insect and the predator who eats the insect, as everything is ecologically connected.

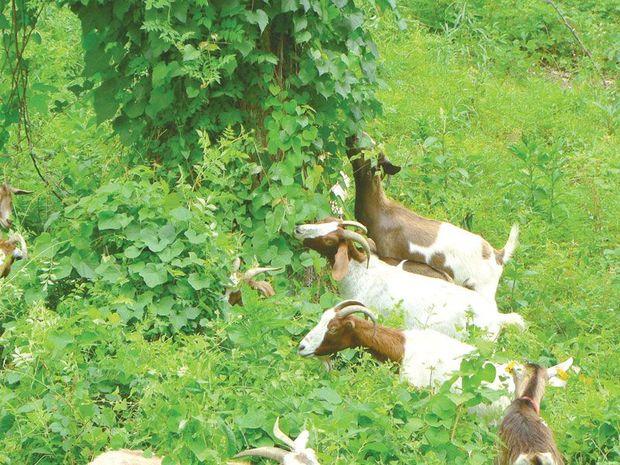

What is a property owner to do about removing invasive plant species? For answers I consulted the experts: Brian Knox of Sustainable Resource Management Inc. and Jennifer Klug Vaccaro of Living Landscape Solutions, LLC. They work with landowners to create stewardship management plans and help manage invasive vegetation removal in both conventional (physical and chemical methods) and unconventional (GOATS!) ways. They also advise on appropriate native plants which usually do not need fertilizers (they recommend compost if you need a fertilizer), pesticides, or watering. Goats are best utilized “when you don’t have anything you want to save.” Phragmites can be daunting and need to be dealt with using chemical herbicides (glyphosate) that are specifically formulated for aquatic uses. Root extraction is not successful as it ends up dispersing the seeds. A toxic chemical permit is required to spray Phragmites with aquatic herbicide in wetlands and can be obtained in Maryland through the Maryland Department of the Environment. Ongoing management is required to prevent regrowth. Vaccaro found that in areas where Phragmites has been successfully removed that native plants returned without planting.

If you visit the Chesapeake Bay Environmental Center in Grasonville, MD (which I highly recommend), you can tour Lake Knapp, a 12-acre lake once dominated by Phragmites, but now home to a wetland complete with diverse native plant and waterfowl species. If you are inspired to become a “weed warrior,” many counties offer specific trainings for volunteers who want to help manage and eradicate invasive plant species in public spaces. There are so many ways for boaters to positively impact the Chesapeake Bay ecosystem, starting in their own backyards!

by Pamela Tenner Kellett