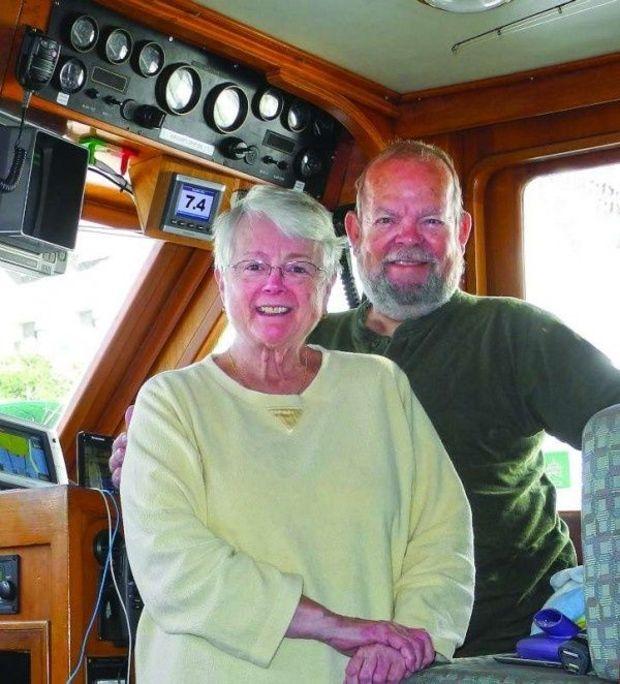

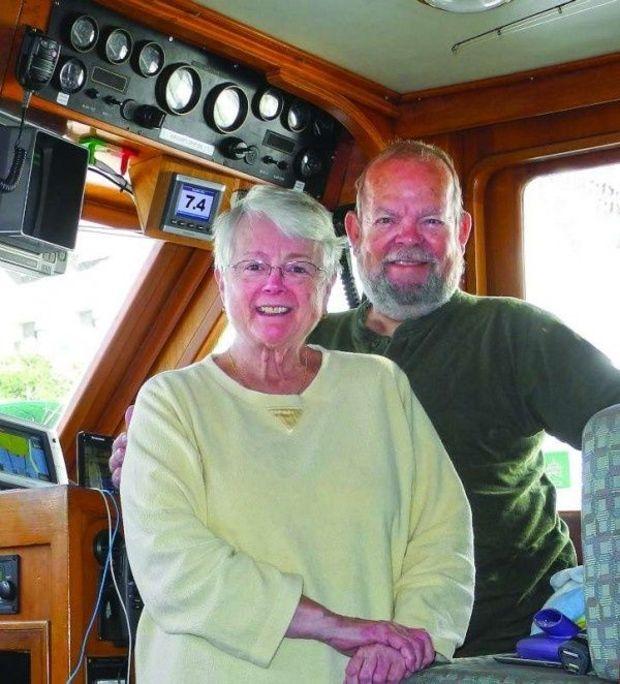

It was November 2012 before Hans and Peggy Bjarno got to realize their dream of becoming snowbirds.

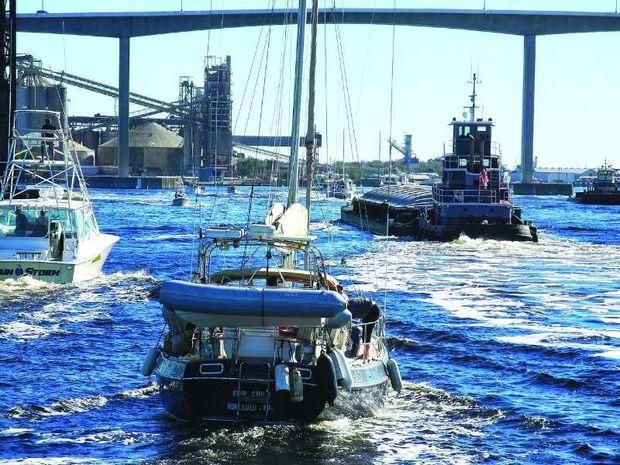

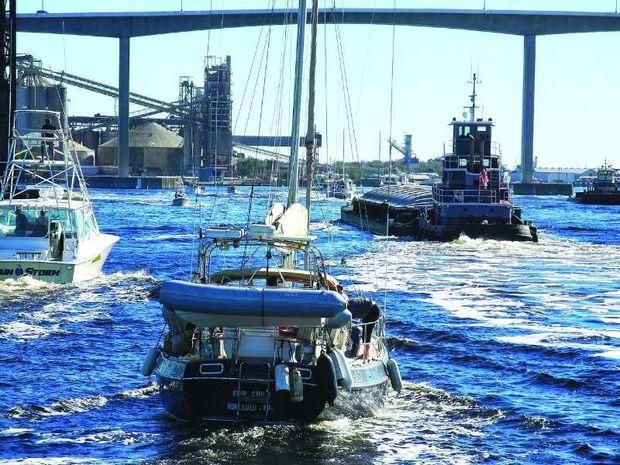

Finally retired, they took their 43-foot Albin trawler

Aqua Vitae down the 1088-mile Intra-Coastal Waterway (ICW) from Norfolk to Miami, and wintered in Marathon, FL, a tiny vacation spot in the Florida Keys. They repeated the trip in 2013 and shortened it in 2014, spending the colder months in Southport, NC. All three trips were made with deliberate speed.

This winter, the Bjarnos are transiting the ICW the way they think it

ought to be done—

slowly. Casting off in mid-October, they motored down the narrow, well-traveled ditch at a leisurely 40 miles a day—half the pace of their previous trips—stopping several days at ports along the way and spending two full months in historic New Bern, NC.

They were scheduled to get to Southport—their destination-port this time around—in early January 2016, and stay there a couple of months before heading back to Baltimore for the start of spring. They don’t expect to churn up much of a wake on the return leg either. “We’ll sort of take our time coming back as well,” Peggy Bjarno says, underscoring the point.

For the Bjarnos, taking it easier makes the annual trip south a lot more fun. Spending fewer hours underway each day enables them to tie up at a marina in late afternoon, without the usual fatigue and the pressure to plan the following day’s trip immediately. There’s plenty of time to check out the nearby facilities, do chores, and go out for a relaxing dinner if they feel like it.

But that’s only the beginning. Being willing to stay in the same marina for more than a single, brief evening gives them leeway to poke around the charming historic towns that dot the coastal area, to shop, and to chat with locals. They also have time to get to know other boaters, often joining them for excursions ashore. “It’s a very different feeling,” Hans says.

Besides their long stays in New Bern and Southport, the Bjarnos spent four nights in Great Bridge, VA; three at the Dismal Swamp state park; two near Oriental, NC; and a couple of nights in Swansboro, NC—all unplanned. “We let the place decide for us,” Peggy says. “If we like where we are, we stay; if not, we don’t.”

It’s the people that make a slow transit south so much more satisfying, the Bjarnos say. Although boaters are friendly enough in short underway conversations on the VHF-FM radio or during brief visits with other slip-renters in late evening, you really get to know and enjoy them if you’re at the same place for a few days or so, Hans asserts.

In New Bern, for example, one of the boaters at their marina had just bought a 200-year-old house in the town and invited five couples in neighboring slips to tour the mansion and walk through the rest of the historic area with him and his wife. “It was nice seeing the town from the perspective of the homeowner,” Peggy says. “We felt a little more included in the town.”

Other boaters they met—some more than once when they stopped at the same ports along the waterway—brought a variety of interesting experiences and perspectives. One couple had just traveled through the Panama Canal, for the 20th time. Another was sailing south from Canada. A third singlehanded a new trawler.

“Boating is a great leveler,” Peggy says. “No matter where we came from or what we had done before, it was as though we were part of a big family.”

This year’s experience is different for another reason. The heavy rains and winds that hit the coastal regions in the south after Hurricane Joaquin in October produced unusually high water levels and redirected channels in many sections of the ICW, leaving some boaters unable to count on their chartplotters or waterway guides.

Sailboaters had the bigger challenges, particularly those with tall-masted boats, who suddenly found their vessels unable to pass under bridges that normally had provided a 65-foot clearance. But powerboaters also ran into problems with silt, debris, and high water-levels that left piers and wharves submerged. They often had to wait several days for storms to pass.

The Bjarnos managed to cope with it all, thanks partly to timely work by the Coast Guard in moving day marks and other navigational aids to reflect changes in waterway conditions, and partly to online apps such as ActiveCaptain, which regularly posts warnings about floating debris, bridge malfunctions, and shifts in the channel.

If anything, the challenges only brought members of this winter’s snowbird contingent even closer than they otherwise might have been. “With conditions what they were, people rafted up three and four boats deep at the marinas,” Peggy recalls. “It was all very cooperative. There was a real sense of community.”

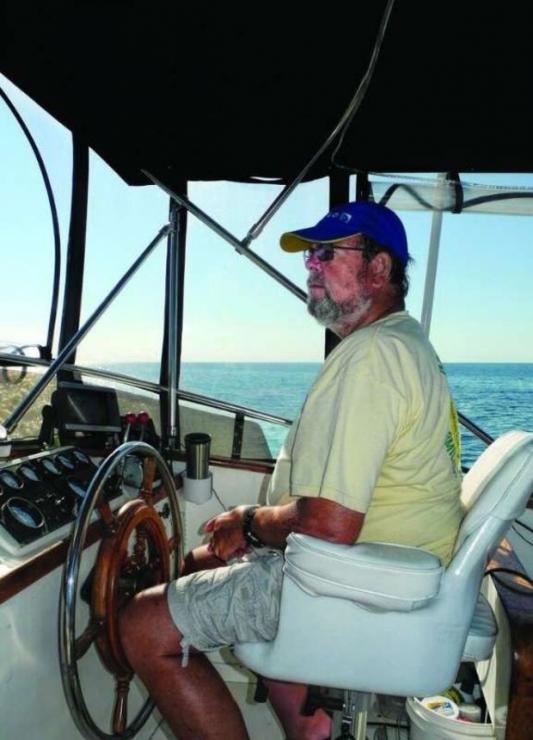

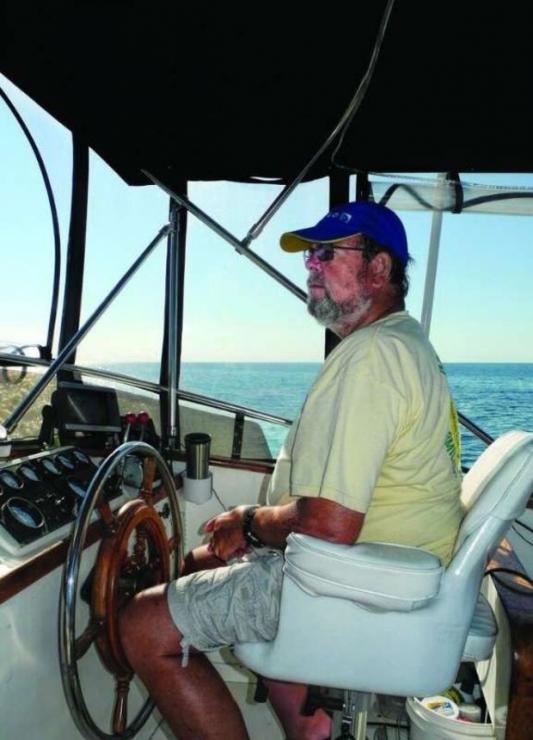

The Bjarnos share their boat duties. Both Hans and Peggy are competent mariners. Both serve as helmsman or navigator, and each helps maintain the vessel’s log. At the same time, Hans is the boat’s knot-tier and line-handler. Peggy, who owned a graphic arts business before they retired, oversees the email letters and photos they send home.

Now in their early 70s, the Bjarnos plan to make one more big change in their snowbird patterns. Sometime this spring, they’ll put their house in Gaithersburg, MD, on the market and become permanent liveaboards, cruising around the Chesapeake Bay during the warm weather and traveling south for the winter, probably tying up at Southport again.

“It seemed we always were in a hurry before,” Peggy says. Now there’ll be no reason to bolt back to Baltimore when spring returns. They’ll be at home wherever they are.

About the Author: Art Pine is a USCG-licensed captain and a longtime Chesapeake Bay powerboater and sailor. This winter, the Bjarnos are transiting the ICW the way they think it ought to be done—slowly. Casting off in mid-October, they motored down the narrow, well-traveled ditch at a leisurely 40 miles a day—half the pace of their previous trips—stopping several days at ports along the way and spending two full months in historic New Bern, NC.

They were scheduled to get to Southport—their destination-port this time around—in early January 2016, and stay there a couple of months before heading back to Baltimore for the start of spring. They don’t expect to churn up much of a wake on the return leg either. “We’ll sort of take our time coming back as well,” Peggy Bjarno says, underscoring the point.

This winter, the Bjarnos are transiting the ICW the way they think it ought to be done—slowly. Casting off in mid-October, they motored down the narrow, well-traveled ditch at a leisurely 40 miles a day—half the pace of their previous trips—stopping several days at ports along the way and spending two full months in historic New Bern, NC.

They were scheduled to get to Southport—their destination-port this time around—in early January 2016, and stay there a couple of months before heading back to Baltimore for the start of spring. They don’t expect to churn up much of a wake on the return leg either. “We’ll sort of take our time coming back as well,” Peggy Bjarno says, underscoring the point.

For the Bjarnos, taking it easier makes the annual trip south a lot more fun. Spending fewer hours underway each day enables them to tie up at a marina in late afternoon, without the usual fatigue and the pressure to plan the following day’s trip immediately. There’s plenty of time to check out the nearby facilities, do chores, and go out for a relaxing dinner if they feel like it.

But that’s only the beginning. Being willing to stay in the same marina for more than a single, brief evening gives them leeway to poke around the charming historic towns that dot the coastal area, to shop, and to chat with locals. They also have time to get to know other boaters, often joining them for excursions ashore. “It’s a very different feeling,” Hans says.

Besides their long stays in New Bern and Southport, the Bjarnos spent four nights in Great Bridge, VA; three at the Dismal Swamp state park; two near Oriental, NC; and a couple of nights in Swansboro, NC—all unplanned. “We let the place decide for us,” Peggy says. “If we like where we are, we stay; if not, we don’t.”

It’s the people that make a slow transit south so much more satisfying, the Bjarnos say. Although boaters are friendly enough in short underway conversations on the VHF-FM radio or during brief visits with other slip-renters in late evening, you really get to know and enjoy them if you’re at the same place for a few days or so, Hans asserts.

In New Bern, for example, one of the boaters at their marina had just bought a 200-year-old house in the town and invited five couples in neighboring slips to tour the mansion and walk through the rest of the historic area with him and his wife. “It was nice seeing the town from the perspective of the homeowner,” Peggy says. “We felt a little more included in the town.”

For the Bjarnos, taking it easier makes the annual trip south a lot more fun. Spending fewer hours underway each day enables them to tie up at a marina in late afternoon, without the usual fatigue and the pressure to plan the following day’s trip immediately. There’s plenty of time to check out the nearby facilities, do chores, and go out for a relaxing dinner if they feel like it.

But that’s only the beginning. Being willing to stay in the same marina for more than a single, brief evening gives them leeway to poke around the charming historic towns that dot the coastal area, to shop, and to chat with locals. They also have time to get to know other boaters, often joining them for excursions ashore. “It’s a very different feeling,” Hans says.

Besides their long stays in New Bern and Southport, the Bjarnos spent four nights in Great Bridge, VA; three at the Dismal Swamp state park; two near Oriental, NC; and a couple of nights in Swansboro, NC—all unplanned. “We let the place decide for us,” Peggy says. “If we like where we are, we stay; if not, we don’t.”

It’s the people that make a slow transit south so much more satisfying, the Bjarnos say. Although boaters are friendly enough in short underway conversations on the VHF-FM radio or during brief visits with other slip-renters in late evening, you really get to know and enjoy them if you’re at the same place for a few days or so, Hans asserts.

In New Bern, for example, one of the boaters at their marina had just bought a 200-year-old house in the town and invited five couples in neighboring slips to tour the mansion and walk through the rest of the historic area with him and his wife. “It was nice seeing the town from the perspective of the homeowner,” Peggy says. “We felt a little more included in the town.”

Other boaters they met—some more than once when they stopped at the same ports along the waterway—brought a variety of interesting experiences and perspectives. One couple had just traveled through the Panama Canal, for the 20th time. Another was sailing south from Canada. A third singlehanded a new trawler.

“Boating is a great leveler,” Peggy says. “No matter where we came from or what we had done before, it was as though we were part of a big family.”

This year’s experience is different for another reason. The heavy rains and winds that hit the coastal regions in the south after Hurricane Joaquin in October produced unusually high water levels and redirected channels in many sections of the ICW, leaving some boaters unable to count on their chartplotters or waterway guides.

Other boaters they met—some more than once when they stopped at the same ports along the waterway—brought a variety of interesting experiences and perspectives. One couple had just traveled through the Panama Canal, for the 20th time. Another was sailing south from Canada. A third singlehanded a new trawler.

“Boating is a great leveler,” Peggy says. “No matter where we came from or what we had done before, it was as though we were part of a big family.”

This year’s experience is different for another reason. The heavy rains and winds that hit the coastal regions in the south after Hurricane Joaquin in October produced unusually high water levels and redirected channels in many sections of the ICW, leaving some boaters unable to count on their chartplotters or waterway guides.

Sailboaters had the bigger challenges, particularly those with tall-masted boats, who suddenly found their vessels unable to pass under bridges that normally had provided a 65-foot clearance. But powerboaters also ran into problems with silt, debris, and high water-levels that left piers and wharves submerged. They often had to wait several days for storms to pass.

The Bjarnos managed to cope with it all, thanks partly to timely work by the Coast Guard in moving day marks and other navigational aids to reflect changes in waterway conditions, and partly to online apps such as ActiveCaptain, which regularly posts warnings about floating debris, bridge malfunctions, and shifts in the channel.

If anything, the challenges only brought members of this winter’s snowbird contingent even closer than they otherwise might have been. “With conditions what they were, people rafted up three and four boats deep at the marinas,” Peggy recalls. “It was all very cooperative. There was a real sense of community.”

The Bjarnos share their boat duties. Both Hans and Peggy are competent mariners. Both serve as helmsman or navigator, and each helps maintain the vessel’s log. At the same time, Hans is the boat’s knot-tier and line-handler. Peggy, who owned a graphic arts business before they retired, oversees the email letters and photos they send home.

Now in their early 70s, the Bjarnos plan to make one more big change in their snowbird patterns. Sometime this spring, they’ll put their house in Gaithersburg, MD, on the market and become permanent liveaboards, cruising around the Chesapeake Bay during the warm weather and traveling south for the winter, probably tying up at Southport again.

“It seemed we always were in a hurry before,” Peggy says. Now there’ll be no reason to bolt back to Baltimore when spring returns. They’ll be at home wherever they are.

About the Author: Art Pine is a USCG-licensed captain and a longtime Chesapeake Bay powerboater and sailor.

Sailboaters had the bigger challenges, particularly those with tall-masted boats, who suddenly found their vessels unable to pass under bridges that normally had provided a 65-foot clearance. But powerboaters also ran into problems with silt, debris, and high water-levels that left piers and wharves submerged. They often had to wait several days for storms to pass.

The Bjarnos managed to cope with it all, thanks partly to timely work by the Coast Guard in moving day marks and other navigational aids to reflect changes in waterway conditions, and partly to online apps such as ActiveCaptain, which regularly posts warnings about floating debris, bridge malfunctions, and shifts in the channel.

If anything, the challenges only brought members of this winter’s snowbird contingent even closer than they otherwise might have been. “With conditions what they were, people rafted up three and four boats deep at the marinas,” Peggy recalls. “It was all very cooperative. There was a real sense of community.”

The Bjarnos share their boat duties. Both Hans and Peggy are competent mariners. Both serve as helmsman or navigator, and each helps maintain the vessel’s log. At the same time, Hans is the boat’s knot-tier and line-handler. Peggy, who owned a graphic arts business before they retired, oversees the email letters and photos they send home.

Now in their early 70s, the Bjarnos plan to make one more big change in their snowbird patterns. Sometime this spring, they’ll put their house in Gaithersburg, MD, on the market and become permanent liveaboards, cruising around the Chesapeake Bay during the warm weather and traveling south for the winter, probably tying up at Southport again.

“It seemed we always were in a hurry before,” Peggy says. Now there’ll be no reason to bolt back to Baltimore when spring returns. They’ll be at home wherever they are.

About the Author: Art Pine is a USCG-licensed captain and a longtime Chesapeake Bay powerboater and sailor.