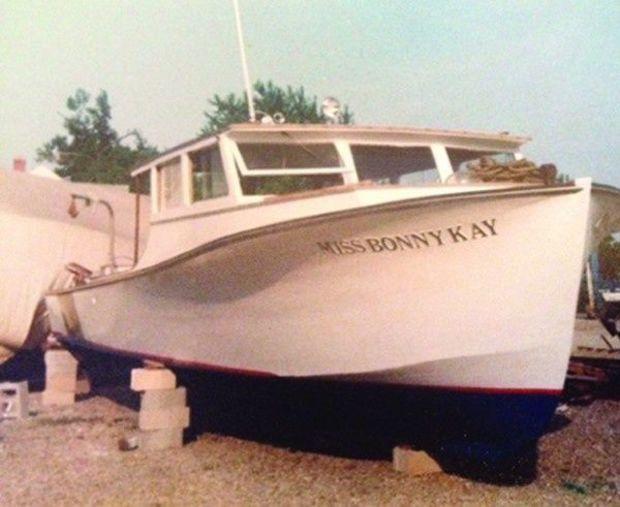

Ever since I was a kid, I can remember hearing all kinds of stories from my grandparents regarding their crabbing days. However, it has not been until more recently that I’ve been able to fully appreciate all that they accomplished. Though they lived in Maryland, they had no background in crabbing. My grandfather was a machinist by trade at Bethlehem Steel, and after the birth of my mother, my grandmother was working on an assembly line at the Lever Brothers factory. At the time, crabbing seemed to them a viable means of secondary income and one that would allow my grandmother to spend more time at home. And so in 1979, they cashed in their rainy day coin collection, took out a loan from the bank, and invested in a 42-foot wooden work boat, custom made on the Eastern Shore. They named her the Miss Bonny Kay after my mother.

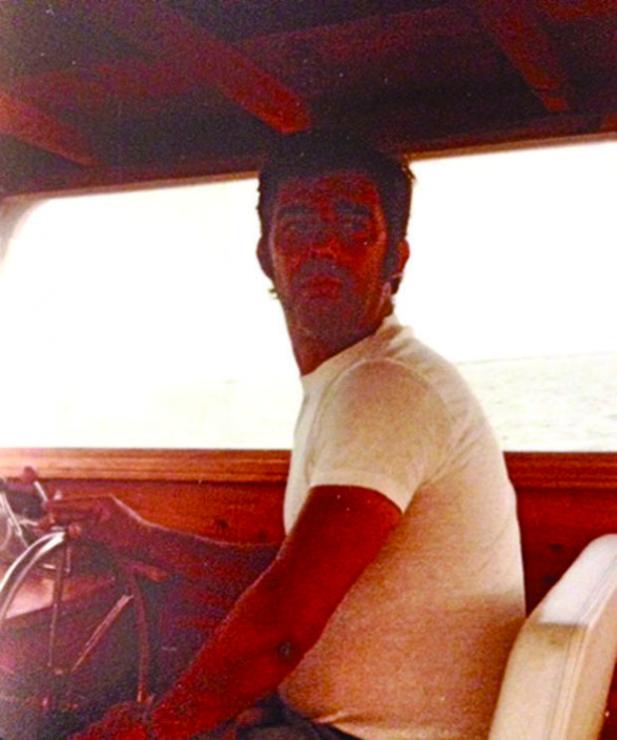

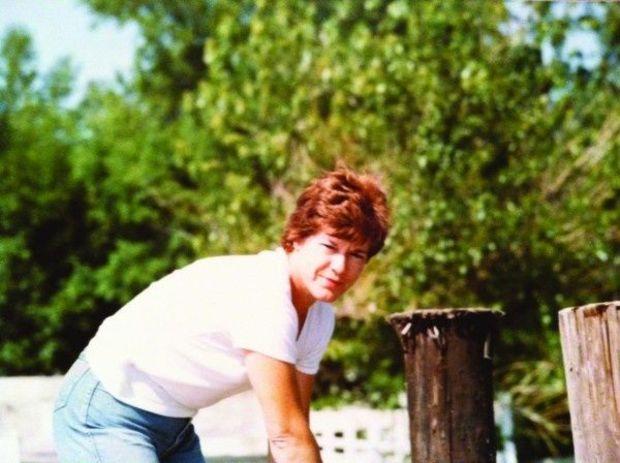

During this early experimental period, my grandmother pulled the pots by herself, while my grandfather drove the boat. Some years later my grandfather would build an automatic pot puller, but in the beginning, it was just the two of them doing the work by hand. My grandmother recalls those initial years with a mixture of humor and disdain, telling me how she used to be “such a frail little thing” before my grandfather put her to work. His joking reply: “Hard work will make your boobs grow bigger.” Her boobs never did get bigger, but her muscles sure did.

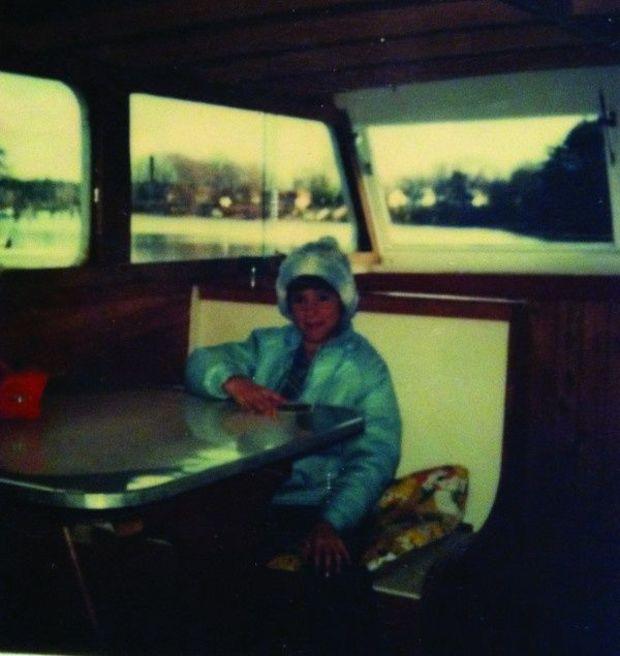

With the business beginning to expand, my grandmother took over the behind-the-scenes work of taking orders and steaming the crabs, while my grandfather, my mother, and two boys from the neighborhood handled the water work. Being on the water was not always as romantic as people liked to think. My mom desperately wanted to be like a normal teenage girl, free from unpleasant tan lines and a job that left her reeking of fish at the end of the day. As if that wasn’t bad enough, the boys would also throw dead fish at her and call her “captain’s brat.”

Despite these hardships, my mother can look back with fondness on those years. Her parents taught her the ways of the water at a very early age, and she soon became “the best crab caller on the Bay,” according to the family. While my grandmother was running the business on land, being on the water was my mother’s special time with her father. It also just so happens that one of those deck-hands, the boy that would call her “captain’s brat,” would several years later become her husband. In the summers, every day but Monday was a work day. Frequent hazards of the job included sun poisoning (because sunscreen did not work as well in those days), jellyfish stings, terrifying squalls, and of course, the daily struggle with pleasure boaters. My grandfather used to refer to sailboaters as the “pretty people,” for they had a knack for “prettily” sailing right through their line of pots.

There was also the time when a rather large cabin-cruiser came speeding up behind the boat while she was underway. Now, in those days, many a waterman used to carry a shotgun on his boat, and though my grandfather never carried one, he did manage to have a hefty toolbox full of wrenches. Nobody knew what this boat wanted, but they were being rather reckless in their approach. My grandfather picked up the biggest wrench from his tool box, only to have the boat’s captain say, “You selling any crabs?” They had got it into their head that they were going to buy crabs right off the boat while the crew was still working. Needless to say, my grandfather had a few choice words and warned the guy about how close he came to having a wrench thrown through his window. That was the last time anyone tried to buy crabs directly off the boat.

These were the stories I had always heard, but then my grandfather passed away. More recently, when I had questions for my college anthropology project, I naturally turned to my grandmother. It was then that I realized just how much of the story had been left out. She loved my grandfather very much but to this day will assert, somewhat cheekily, that it is really the women who run the business and the men who “just drive the boats.” In her own words: “It was a riot! It was chaos! That’s what it was. It seemed like the minute you thought you had time to take a breather, or do something you’d like, something always interrupted it. You just had no life of your own. The women, anyway. Like I said, once our boys got off that boat, hell, you’d never see them anymore. I ran the business, I ran the business in here. Them men just get in the boat and drive the boat. Everybody else does the pot pulling. The wife goes crazy with the weirdo customers. I steamed crabs; I answered the phone around the clock; I tried raising kids, running a house. I had to get away.They were driving me nuts! And that’s just like when I said at night when I went down and looked at them soft crabs, I said, ‘Beautiful swimmers my ass!’ I didn’t get no sleep. It was a real riot! A riot for the women.”

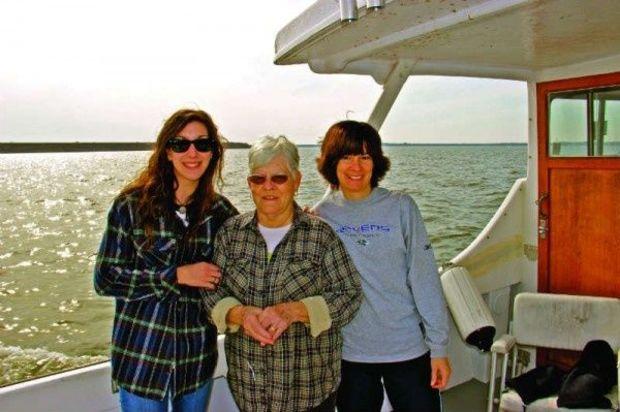

All together, my grandparents crabbed the Chesapeake Bay for about 20 years. I have the utmost respect for both of them, for what they accomplished and equally for what they endured. My grandmother grew up in Pittsburgh, PA, and moved to Middle River when she was only 16. She felt as if she had been stranded on “the end of the earth,” but she soon learned the ways of the water and taught my mother at an even earlier age. My mother subsequently had my brother and me in the Bay practically before we could walk, and so I am equally familiar with the romanticized portraits of the watermen who fish its waters. I have romanticized them myself.

That is ultimately why I wanted to tell my grandparents’ story in all of its gritty detail. They had to take the good with the more often bad but managed to turn an experimental endeavor into a thriving business. I have also noticed that the women’s stories are not told nearly as often as the men’s are, for their behind-the-scenes work is often deemed less important. The women who fish the Bay’s waters, either independently or alongside their husbands and fathers, have just as much a right for their stories to be heard as the men do. In recounting this shortened version of my own family’s experiences, I can only hope to begin to bridge this ethnographic gap.

I will always see the Chesapeake Bay as one of my favorite places in the world, but in praising it I must also be honest about it. My younger brother recently acquired his captain’s license and a boat in hopes of taking up the family business, but the business is not what it used to be. To be a waterman is not always the romantic, picturesque image that people so often place upon it. It can be, but it can also be an incredibly taxing occupation that is beginning to suffer more and more in recent years with declining fish stocks and raising gas prices. In order to preserve this livelihood, we must recognize it for its glories as well as for its hardships. It is only then that we can begin to hope to preserve this quintessential tradition of our beloved estuary.

About the Author: A senior anthropology and English major at St. Mary’s College of Maryland, Kaylie Jasinski hails from Middle River and enjoys recreational boating and crabbing.