Not long ago I read an article in a boating magazine entitled, “Oil Analysis Made Simple.” It struck a chord because as a trained oil analyst (what the industry refers to as a tribologist), I know from experience as well as formal training that oil analysis (formally referred to as fluid analysis, which also includes coolant, fuel, and hydraulic fluid) is complex and fraught with opportunity for sampling errors and misinterpretation of reports. No wonder the science of oil analysis is frequently dismissed by industry professionals as unreliable; in many cases they have reason to question the results.

In Practice

Lubricating oil is the very lifeblood of an engine. Without it, gears and bearings would quickly overheat, seize, and grind themselves to pieces. In addition to lubrication and heat removal, as oil courses through an engine, it picks up and carries with it any and all contaminants, from moisture and carbon to metal, coolant, and fuel, all of which can be identified and analyzed. In doing so, and when carried out properly and accurately, this analysis can reveal a great deal about engines and other equipment. I frequently refer to this analysis as the mechanic’s (and boat owners’/buyers’) crystal ball.

The return on investment where fluid analysis is concerned can be substantial. Analyzing a few ounces of crankcase oil, for instance, can yield reams of information about the current health of an engine and how it’s been maintained throughout its life. For instance, sodium (typically but not always considered an external contaminant, as it is contained in some coolant mixtures), when found in an engine’s lubricating oil, may be indicative of ingestion of salt-laden mist (this can happen if spray is ingested into an engine room air intake). By contrast, wear metals such as iron, chrome, nickel, copper, lead, tin, and aluminum, each tell a different story about a component within the engine, from pistons and rings to bearings and valves.

The quantity of metal in a sample for instance, measured in parts per million, when compared to the number of hours accrued by the sample oil, determines whether there is cause for concern. Still other contaminants, such as diesel fuel and soot, and imbalances, such as total base number and viscosity, can indicate malfunctioning fuel injection systems, use of the incorrect stock oil, or simply oil that is old, worn out, and acidified.

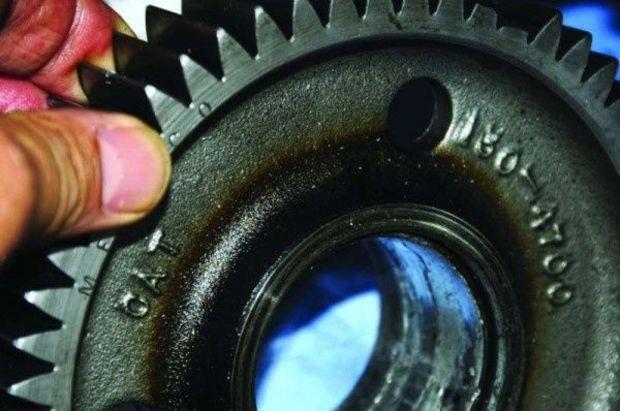

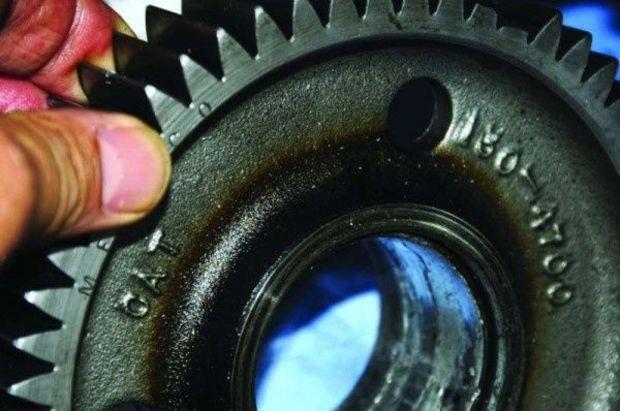

Fluid detective work doesn’t end with crankcase oil. Transmission and hydraulic fluid and coolant are also fertile ground for this sort of testing. Transmission fluid analysis can often detect issues with bearings, clutches, shift mechanism adjustment, damaged gears, or overheating. Many transmissions include some type of cooler; however, if it’s not working properly, oil can overheat and lose some of its lubricating properties. Coolant includes additives that inhibit rust and corrosion as well as control pH; however, over time these become depleted.

Common wisdom dictates that cooling systems be flushed and coolant replaced every two years. However, that’s likely conservative. An analysis of the coolant can stave off this service if it’s unnecessary, often paying for itself. The same is true of hydraulic fluid; if the system in which it’s used is working properly, and not exposed to outside contaminants, it may remain serviceable for years and thousands of hours of run time.

Avoiding the Most Common Analysis Errors

Avoiding the Most Common Analysis Errors

As valuable as fluid analysis is, it isn’t perfect, and in the hands of an inexperienced wannabe tribologist, misinterpretation is all too easy. For example, a client once contacted me, distraught over the results of a transmission fluid analysis report. They showed very high levels of copper, so high that the analysis lab had flagged them in red.

After exchanging a few emails with the transmission manufacturer, however, I determined that the clutches were sintered copper alloy and therefore, these high copper readings were not abnormal. The lesson here is the value of the amount of data a lab has accumulated on an engine, transmission, or other type of equipment is important when it comes to alerting the user to potential trouble.

Another all too common, perhaps the most common, error is one I refer to as flag fixation, wherein those reviewing oil analysis reports simply scan them for red, yellow, and green flags, or indications of trouble, or the absence thereof. If no red or yellow flags are present, he or she pronounces the equipment from which the report was derived as healthy. This practice is both dangerous and, for industry pros such as mechanics and surveyors, irresponsible.

On one occasion, I reviewed an analysis report for a client, one the mechanic had passed with an “it’s all good,” thanks to the lack of red and yellow flags. Yet, when I scrutinized the figures, I realized that when completing the sample form, he’d inadvertently reversed the lube time, the number of hours on the oil, with the unit time, the number of hours on the engine. As a result, the lab believed the oil had accrued nearly 800 hours, while the engine itself had only 150, an impossibility, of course, yet the lab technician inputting the data failed to capture the discrepancy. The threshold for contamination for oil that has accumulated this many hours is extremely high and failed to trigger a red flag; however, when the correct lube time was later inserted and the data re-run by the lab, the engine’s report went from green to red. Much like the old computer programming axiom, garbage in garbage out, oil analysis is only as good as the accuracy of the data supplied to the lab.

Yet another area where analysis often goes awry involves sampling technique. For example, if a vacuum pump and hose are used to draw a sample and the latter’s intake is dragged across the bottom of an oil pan in the process, it is likely to show elevated wear metal, material that has accumulated over the course of hundreds or thousands of hours (referencing the sample tube to the dip stick can prevent this sort of error). It is for this reason that many commercial users rely on sample valves installed in oil galleries, rather than vacuum pumps and tubes; when drawing crankcase oil samples, the valve delivers oil as it’s circulating through the engine, offering the most accurate representation of its condition.

Whether you are taking samples yourself or relying on a professional, make certain good sampling technique is practiced, including avoidance of cross contamination (vacuum tubes must never be reused). If a vacuum pump is being used, avoid splashing oil up into the pump, which is yet another source of cross contamination, and label each bottle the moment it is capped to prevent mixing up samples.

I routinely hear, particularly from brokers, about the questionable validity of a single analysis, as opposed to engines whose oil has been sampled regularly. While there is a value to interpretation of trends in oil analysis, single samples, especially where pre-purchase surveys are concerned, are both useful and valid. Don’t let anyone talk you out of them or dismiss the results, provided samples were taken properly, forms filled in accurately, and reports reviewed carefully.

About the Author: Steve D’Antonio consults for boat owners and buyers, boat builders, and others in the industry. Visit

stevedmarine.com for his weekly technical columns.

The return on investment where fluid analysis is concerned can be substantial. Analyzing a few ounces of crankcase oil, for instance, can yield reams of information about the current health of an engine and how it’s been maintained throughout its life. For instance, sodium (typically but not always considered an external contaminant, as it is contained in some coolant mixtures), when found in an engine’s lubricating oil, may be indicative of ingestion of salt-laden mist (this can happen if spray is ingested into an engine room air intake). By contrast, wear metals such as iron, chrome, nickel, copper, lead, tin, and aluminum, each tell a different story about a component within the engine, from pistons and rings to bearings and valves.

The quantity of metal in a sample for instance, measured in parts per million, when compared to the number of hours accrued by the sample oil, determines whether there is cause for concern. Still other contaminants, such as diesel fuel and soot, and imbalances, such as total base number and viscosity, can indicate malfunctioning fuel injection systems, use of the incorrect stock oil, or simply oil that is old, worn out, and acidified.

The return on investment where fluid analysis is concerned can be substantial. Analyzing a few ounces of crankcase oil, for instance, can yield reams of information about the current health of an engine and how it’s been maintained throughout its life. For instance, sodium (typically but not always considered an external contaminant, as it is contained in some coolant mixtures), when found in an engine’s lubricating oil, may be indicative of ingestion of salt-laden mist (this can happen if spray is ingested into an engine room air intake). By contrast, wear metals such as iron, chrome, nickel, copper, lead, tin, and aluminum, each tell a different story about a component within the engine, from pistons and rings to bearings and valves.

The quantity of metal in a sample for instance, measured in parts per million, when compared to the number of hours accrued by the sample oil, determines whether there is cause for concern. Still other contaminants, such as diesel fuel and soot, and imbalances, such as total base number and viscosity, can indicate malfunctioning fuel injection systems, use of the incorrect stock oil, or simply oil that is old, worn out, and acidified.

Fluid detective work doesn’t end with crankcase oil. Transmission and hydraulic fluid and coolant are also fertile ground for this sort of testing. Transmission fluid analysis can often detect issues with bearings, clutches, shift mechanism adjustment, damaged gears, or overheating. Many transmissions include some type of cooler; however, if it’s not working properly, oil can overheat and lose some of its lubricating properties. Coolant includes additives that inhibit rust and corrosion as well as control pH; however, over time these become depleted.

Common wisdom dictates that cooling systems be flushed and coolant replaced every two years. However, that’s likely conservative. An analysis of the coolant can stave off this service if it’s unnecessary, often paying for itself. The same is true of hydraulic fluid; if the system in which it’s used is working properly, and not exposed to outside contaminants, it may remain serviceable for years and thousands of hours of run time.

Fluid detective work doesn’t end with crankcase oil. Transmission and hydraulic fluid and coolant are also fertile ground for this sort of testing. Transmission fluid analysis can often detect issues with bearings, clutches, shift mechanism adjustment, damaged gears, or overheating. Many transmissions include some type of cooler; however, if it’s not working properly, oil can overheat and lose some of its lubricating properties. Coolant includes additives that inhibit rust and corrosion as well as control pH; however, over time these become depleted.

Common wisdom dictates that cooling systems be flushed and coolant replaced every two years. However, that’s likely conservative. An analysis of the coolant can stave off this service if it’s unnecessary, often paying for itself. The same is true of hydraulic fluid; if the system in which it’s used is working properly, and not exposed to outside contaminants, it may remain serviceable for years and thousands of hours of run time.

Avoiding the Most Common Analysis Errors

As valuable as fluid analysis is, it isn’t perfect, and in the hands of an inexperienced wannabe tribologist, misinterpretation is all too easy. For example, a client once contacted me, distraught over the results of a transmission fluid analysis report. They showed very high levels of copper, so high that the analysis lab had flagged them in red.

After exchanging a few emails with the transmission manufacturer, however, I determined that the clutches were sintered copper alloy and therefore, these high copper readings were not abnormal. The lesson here is the value of the amount of data a lab has accumulated on an engine, transmission, or other type of equipment is important when it comes to alerting the user to potential trouble.

Another all too common, perhaps the most common, error is one I refer to as flag fixation, wherein those reviewing oil analysis reports simply scan them for red, yellow, and green flags, or indications of trouble, or the absence thereof. If no red or yellow flags are present, he or she pronounces the equipment from which the report was derived as healthy. This practice is both dangerous and, for industry pros such as mechanics and surveyors, irresponsible.

On one occasion, I reviewed an analysis report for a client, one the mechanic had passed with an “it’s all good,” thanks to the lack of red and yellow flags. Yet, when I scrutinized the figures, I realized that when completing the sample form, he’d inadvertently reversed the lube time, the number of hours on the oil, with the unit time, the number of hours on the engine. As a result, the lab believed the oil had accrued nearly 800 hours, while the engine itself had only 150, an impossibility, of course, yet the lab technician inputting the data failed to capture the discrepancy. The threshold for contamination for oil that has accumulated this many hours is extremely high and failed to trigger a red flag; however, when the correct lube time was later inserted and the data re-run by the lab, the engine’s report went from green to red. Much like the old computer programming axiom, garbage in garbage out, oil analysis is only as good as the accuracy of the data supplied to the lab.

Avoiding the Most Common Analysis Errors

As valuable as fluid analysis is, it isn’t perfect, and in the hands of an inexperienced wannabe tribologist, misinterpretation is all too easy. For example, a client once contacted me, distraught over the results of a transmission fluid analysis report. They showed very high levels of copper, so high that the analysis lab had flagged them in red.

After exchanging a few emails with the transmission manufacturer, however, I determined that the clutches were sintered copper alloy and therefore, these high copper readings were not abnormal. The lesson here is the value of the amount of data a lab has accumulated on an engine, transmission, or other type of equipment is important when it comes to alerting the user to potential trouble.

Another all too common, perhaps the most common, error is one I refer to as flag fixation, wherein those reviewing oil analysis reports simply scan them for red, yellow, and green flags, or indications of trouble, or the absence thereof. If no red or yellow flags are present, he or she pronounces the equipment from which the report was derived as healthy. This practice is both dangerous and, for industry pros such as mechanics and surveyors, irresponsible.

On one occasion, I reviewed an analysis report for a client, one the mechanic had passed with an “it’s all good,” thanks to the lack of red and yellow flags. Yet, when I scrutinized the figures, I realized that when completing the sample form, he’d inadvertently reversed the lube time, the number of hours on the oil, with the unit time, the number of hours on the engine. As a result, the lab believed the oil had accrued nearly 800 hours, while the engine itself had only 150, an impossibility, of course, yet the lab technician inputting the data failed to capture the discrepancy. The threshold for contamination for oil that has accumulated this many hours is extremely high and failed to trigger a red flag; however, when the correct lube time was later inserted and the data re-run by the lab, the engine’s report went from green to red. Much like the old computer programming axiom, garbage in garbage out, oil analysis is only as good as the accuracy of the data supplied to the lab.

Yet another area where analysis often goes awry involves sampling technique. For example, if a vacuum pump and hose are used to draw a sample and the latter’s intake is dragged across the bottom of an oil pan in the process, it is likely to show elevated wear metal, material that has accumulated over the course of hundreds or thousands of hours (referencing the sample tube to the dip stick can prevent this sort of error). It is for this reason that many commercial users rely on sample valves installed in oil galleries, rather than vacuum pumps and tubes; when drawing crankcase oil samples, the valve delivers oil as it’s circulating through the engine, offering the most accurate representation of its condition.

Whether you are taking samples yourself or relying on a professional, make certain good sampling technique is practiced, including avoidance of cross contamination (vacuum tubes must never be reused). If a vacuum pump is being used, avoid splashing oil up into the pump, which is yet another source of cross contamination, and label each bottle the moment it is capped to prevent mixing up samples.

Yet another area where analysis often goes awry involves sampling technique. For example, if a vacuum pump and hose are used to draw a sample and the latter’s intake is dragged across the bottom of an oil pan in the process, it is likely to show elevated wear metal, material that has accumulated over the course of hundreds or thousands of hours (referencing the sample tube to the dip stick can prevent this sort of error). It is for this reason that many commercial users rely on sample valves installed in oil galleries, rather than vacuum pumps and tubes; when drawing crankcase oil samples, the valve delivers oil as it’s circulating through the engine, offering the most accurate representation of its condition.

Whether you are taking samples yourself or relying on a professional, make certain good sampling technique is practiced, including avoidance of cross contamination (vacuum tubes must never be reused). If a vacuum pump is being used, avoid splashing oil up into the pump, which is yet another source of cross contamination, and label each bottle the moment it is capped to prevent mixing up samples.

I routinely hear, particularly from brokers, about the questionable validity of a single analysis, as opposed to engines whose oil has been sampled regularly. While there is a value to interpretation of trends in oil analysis, single samples, especially where pre-purchase surveys are concerned, are both useful and valid. Don’t let anyone talk you out of them or dismiss the results, provided samples were taken properly, forms filled in accurately, and reports reviewed carefully.

About the Author: Steve D’Antonio consults for boat owners and buyers, boat builders, and others in the industry. Visit stevedmarine.com for his weekly technical columns.

I routinely hear, particularly from brokers, about the questionable validity of a single analysis, as opposed to engines whose oil has been sampled regularly. While there is a value to interpretation of trends in oil analysis, single samples, especially where pre-purchase surveys are concerned, are both useful and valid. Don’t let anyone talk you out of them or dismiss the results, provided samples were taken properly, forms filled in accurately, and reports reviewed carefully.

About the Author: Steve D’Antonio consults for boat owners and buyers, boat builders, and others in the industry. Visit stevedmarine.com for his weekly technical columns.