Lover’s Lane is a sleepy little lane in Deltaville, VA, where it appears as if nothing more exciting than the grass growing and flowers blooming is happening. Appearances can be deceiving. Behind the closed doors of a barn-like building on Lovers Lane a tradition is being carried on. Captain Willard Norris is still building deadrise boats after five decades and is passing on his skills to his grandson Ryan.

In the bygone days, when Jackson Creek was a center for deadrise boat building, the echoes of hammers, the creak of hand saws, the scrape of the foot adz, and the whining of block and tackle ropes straining filled the air. Back in those days just about all commercial boats were powered by sail. Intermingled with the snap of sails taking the wind was the pop-pop of make-and-brake engines and converted-automobile engines to create a cacophony of nautical sounds. Jackson Creek has always been an ideal place to build and repairs boats.

A boy in three boatyards

The internal combustion engine, with all its noise and odors, won the battles between sail and mechanical power right about the time young Willard was old enough to hang around boats. While most youngsters his age played in meadows and school grounds, he found his playgrounds at three separate boatyards owned by his grandfather Ed Deagle and his uncles Pete Deagle and Alfred Norris. There were lots of things to amuse a young boy in those three boatyards. Ropes and blocks, power saws, and screw jacks. It was in those yards where Willard played that the art of building deadrise boats was honed to perfection. He was eager to learn and joined in the work whenever he was allowed to steady a plank or tote a tool.

Willard was born and raised on Lovers Lane, where many of the legendary deadrise builders of Jackson Creek did their work on its shores. He would spend hours watching John Wright build 65-foot-long boats right there on the shore. Wright used only hand tools, a foot adz, hand planes, rip-saws, and nothing more. Willard was amazed to see that Wright did not use power saws or power-anything. Norris counts himself very fortunate to have his choice of master boatbuilders to watch. He can point out the places along Lovers Lane where boats were built by Wright and Ladd, Tom and Lewis Wright, along with the boatbuilding sites of Rob Dudley, Hugh Norris, Willie Marchant, and Alfred Norris.

Working at the marine railway

At 16, Norris went to work summers for his uncle Lee Deagle, the owner of Deagle and Son Marine Railway (now Chesapeake Bay Marine Railways), one of the largest marine railways in the area. He said, “There were so many woodworkers there in those days working on boats that they were happy to give you advice and share a tip on just how to do something.” Norris’s uncle, Alfred, taught him how to set up and build a boat. His uncle, Lee, taught him how to work with wood. He learned how to build deadrise boats literally from the ground up. There were neither classes to attend nor plans to follow. The learning came from watching skilled woodworkers use their primitive tools to turn raw wood into the frames, planks, and keelsons of deadrise boats, which are built by “rack of eye.”

By the tender age of 18 Willard had married Shirley Harrow. Now having a wife to provide for, Willard set out to build himself a round-stern deadrise boat so he could go patent-togging for oysters. In the beginning, there was no shed behind his house. So, like many boatbuilders, he set to work in the open air. He laid out the boat in the backyard as he had been taught to do by his uncles. Wright would come over every morning, check over the work Willard had done the previous day and advise him on how he was building the boat. Wright had a special interest in Willard because Wright’s wife, Blanche, was Shirley Norris’s aunt.

Willard joined the Virginia Marine Resources Commission (VMRC) in the 60s where he worked days while still building boats and fishing at night and on his days off. Shirley Norris told me Willard worked out in the boat shed until late in the evening. She said, “I used to shout out to him, if you don’t come into the house I am going to pull the main switch.” She said he would respond, “You are an unusual woman. Most women fuss because their husbands don’t want to work, but you fuss because I want to work.”

Boat building in the living room

When they were first married in 1945, for Willard and Shirley money was tight. They jumped at the chance to build a boat despite the fact Willard did not yet have his workshop built. A man came along and asked him to build an 18-foot skiff. They needed money to buy lumber and wallboard to finish the house, so Willard set out to build a skiff in the living room. The money he got from this boat enabled the young couple to buy the materials they needed to finish the living room.

Willard’s first big boat came in 1946. It was a 38-foot round-stern deadrise boat. He used that boat to harvest oysters using a patent tongue. Three years later he bought a crab dredge boat, and he did that until the Bay got overrun with mussels. Eventually he went to work for VMRC and was in charge of buying and maintaining all their boats. He retired after 30 years with VMRC. All the while he kept building boats and fishing. By the 60s, Willard had switched over to building box-stern deadrise boats in the 40-foot range, which provided more work space for watermen.

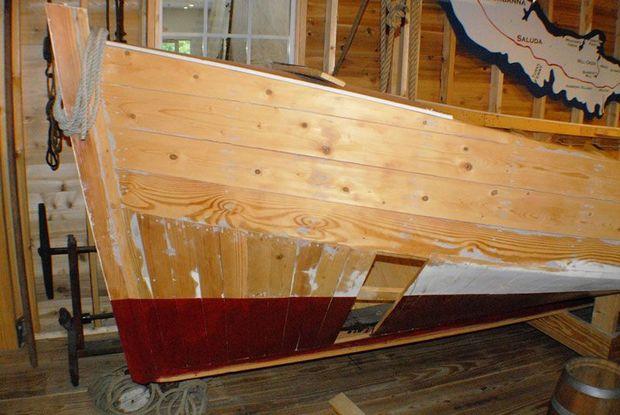

Despite the fact that he was diagnosed with pancreatic cancer and given only months to live, Shirley says that even when he was very sick and undergoing chemotherapy, he would work in his boat shed building skiffs in back of their home on Lovers Lane. In 2001, Norris took on the task of building a 32-foot deadrise in his shed. He called it the Last One. Norris’s boat shed is typical of the kind of buildings most boatbuilders used back in the heyday of wooden boats. Chock-full of tools, it is almost a museum of old tools, some from retired boatbuilders. Hanging from the rafters is an old sailing ship block and tackle Willard has used for years to hoist up and turn over the basic deadrise frame once it was all assembled with the keelson in place.

The Rainbow Chaser

The word in deadrise boat circles has been for many years that Willard builds one of the best Chesapeake Bay deadrise boats available. Not surprisingly many of his boats are in regular use 30 years later. One of the most famous of these is a boat named the Rainbow Chaser.

Willard built her for Sonny Gay who was a working waterman. When he passed away in 1998, his son Shannon Gay took over the boat. Shannon told me that when his dad was alive they would race the boat at Harborfest. The original boat was powered with a 6V53 Detroit Diesel engine which was 210 hp and won races then. Shannon said, “Racing Rainbow Chaser was my dad’s hobby. He loved to race that boat, and he was so very proud of her. When he was having the boat built, he would take us to Willard’s shop in Deltaville every other weekend to check on the progress. Dad had owned an older deadrise, but he wanted one built to his liking.”

Shannon and his father got serious about workboat racing in 1986. They would sit at the dinner table many evenings and talk about all the things they were going to do to make the boat faster, check over photos, and make plans. To make it even faster, Shannon fitted Rainbow Chaser with a Volvo Penta TAMD74 diesel engine which delivers 500 hp. The increase horsepower made it a winner. Shannon said a lot of the boats he races against have twice the horsepower and some are much lighter fiberglass boats, but he pretty much beats them most of the time. He is confident he can beat any boat similar to his. Shannon has raced and won at Harborfest, Yorktown, and Poquoson.

Last year Shannon arranged for three generations of Norrises, Willard, his son Tuna, and his grandson to ride in Rainbow Chaser during a race at Harborfest. Using his expertise in marine engine power plants, Shannon has been able to turn Willard’s old deadrise into a championship workboat racer. Today Willard is semi-retired from boat building. That, of course, does not mean he does not spend a great deal of his time working on deadrise boats and teaching his skills to his grandson. Thankfully, the time-honored skills involved in of rack-of-eye building deadrise boats will be carried on.

by Captain Bob Cerullo